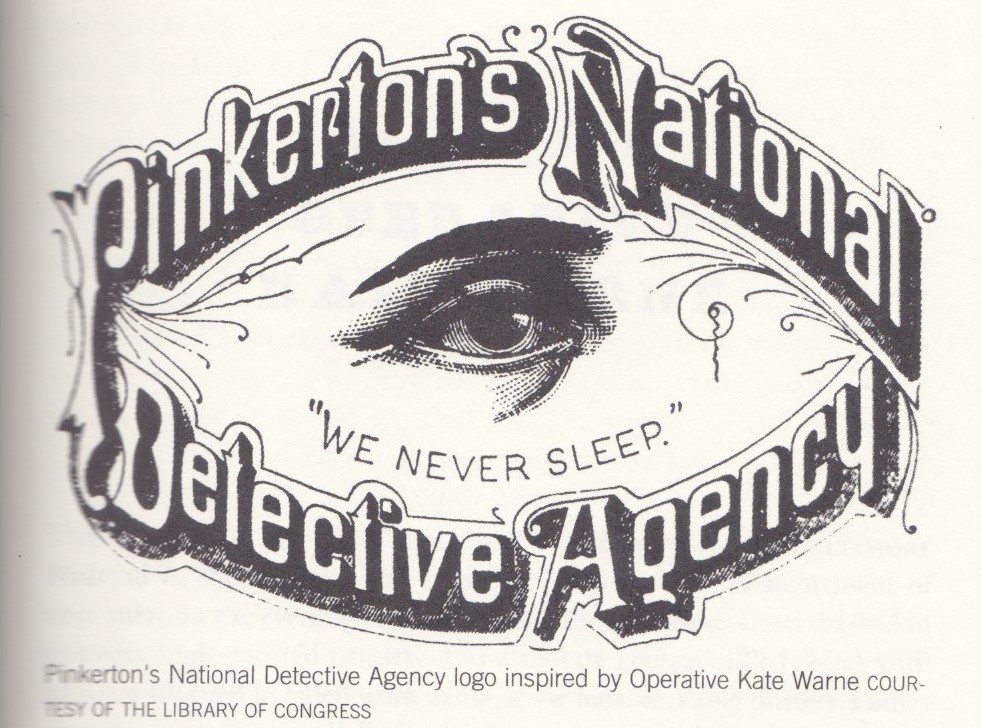

Historical Context for Walker: Independence – Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency

Pinkerton Men and Women

Allan Pinkerton believed that the only quality a person was required to have to be a detective was a good dose of common sense. Most other factors fell to the wayside, giving him the ability to see beyond race and gender in a way few others did at the time. Pinkerton operatives came from all walks of life. Employment at the agency was rather fluid, with some operatives being lifers while many others worked there as a steppingstone to police work, trying out a new vocation, or even just as something to do between jobs. It was actually a common practice for the wives of regular operatives to take on the odd railroad employee testing shift. Because of the flexibility of Pinkerton hiring practices, the operatives hired to work at the agency were an incredibly diverse group. I took a look at the histories of some of these men and women who made their mark on the agency, and I wanted to share some of their stories here.

Kate Warne

Kate Warne is credited with being the first female detective. She was hired at the Pinkerton National Detective Agency in 1856 after she responded to a newspaper ad for new detectives. Though Pinkerton was hesitant to hire her at first (who had ever heard of a woman detective?), she provided many sound arguments on how a woman could be useful in the field. During that initial interview she said that “Women could be most useful in worming out secrets in many places that would be impossible for a male detective…A woman would be able to befriend the wives and girlfriends of suspected criminals and gain their confidence. Men become braggarts when they are around women who encourage them to boast. Women have an eye for detail and are excellent observers.” (Enss, 2017). Pinkerton hired her the next day.

Kate Warne went on to become one of Pinkerton’s best detectives. She took on her many undercover roles with ease, including identities such as L.L. Lucillle the egyptian fortune teller (who unveiled both a successful and an attempted murder by an ambitious politician) and Mrs. M. Barkley (the identity she used to smuggle president-elect Abraham Lincoln past his would-be assassins in Baltimore). After more women were hired, she was placed in charge of all female operatives in 1861 and was responsible for training them and overseeing their work. Though female detectives were frowned upon and used to slander Pinkerton as a philanderer, Kate more than proved herself to be worth her pay. She was an excellent actress who used her skills to gain the confidence of suspects and their wives alike, leading to confessions and gleaning more evidence than some of her male coworkers. Pinkerton wrote in his memoire that “she succeeded far beyond my utmost expectations.” (Enss, 2017).

Kate died in 1868. The cause of death is unknown but many believe it was a result of a lingering illness. When this was announced in the news, the Philadelphia Press noted that “As she lived, so she died, a fearless, pure, and devoted woman.” She is currently buried at the Graceland Cemetery in Chicago with other Pinkerton agents.

[Watercolor portrait of Kate Warne, courtesy of the Chicago History Museum]

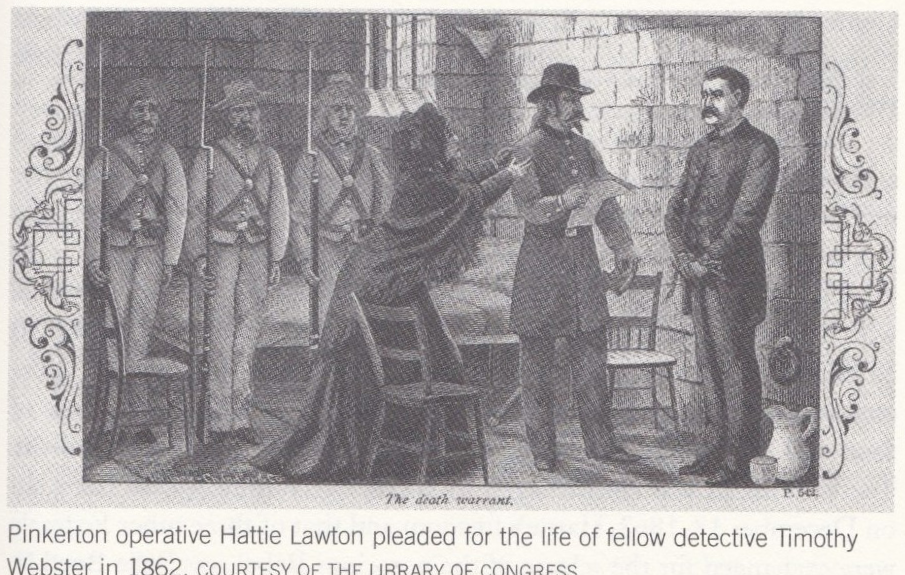

Hattie Lewis Lawson

Hattie Lawson was the second female detective hired by Pinkerton in 1860. Some historians believe she may have also been the first mixed-race female detective. There is no firm evidence of this, but some believe that Hattie and Pinkerton first met while he was sheltering her family as they prepared for the final leg of their journey on the Underground Railroad. However they may have met, Hattie proved herself to be a useful detective and spy for the Secret Service. Pinkerton considered her to be a key player in many investigations.

One of her more dangerous missions involved posing as a married couple with Timothy Webster in order to learn information on Confederate military movements. After Timothy fell ill, she used her connections among her “husbands” Confederate “friends” to throw parties and gain access to forts and encampments where she might learn information. She was joined by John Scobell, who posed as a servant so he could blend in and hear more information.

Hattie was arrested on this mission after a previously captured Pinkerton agent revealed her and Timothy’s identities. She was sentenced to a year in prison and made friends with Elizabeth van Lew, who petitioned for her release. Near the end of 1862, Hattie was released with 3 other federal agents in exchange for Confederate spy Belle Boyd.

John Scobell

John Scobell was a former slave who chose to risk his life as a spy for the Secret Service during the Civil War. Pinkerton hired him in 1861.

While Pinkerton may have been able to look past John’s race, most of the rest of society would not. John used this to his advantage while spying behind Confederate lines by posing as a servant. It was easy for him to blend into the background at parties or while visiting Confederate forts with his “masters” and overhear important conversations regarding plans for the future and military movements. He made regular reports back to Washington on the information he uncovered.

In one case working with Hattie Lawson, he not only posed as her groom (horse attendant) but also acted as her bodyguard on a mission to meet with Union troops, a mission that was nearly jeopardized by a Confederate counterspy.

Timothy Webster

Timothy Webster was a brave Pinkerton Operative who tragically lost his life during the Civil War.

Webster had infiltrated the Sons of Liberty, a secret organization within the Confederacy, and was trusted enough among them to be made courier of important documents between members and chapters, documents that made it into the hands of both the Confederates and the Union. Unfortunately for him, long nights riding out in the cold and stormy weather did a number on his health and he fell ill after one too many trips. He was working with Hattie Lawson at the time, posing as her husband, and she was able to care for him, but his condition did not get better.

While he was ill, he started sending fewer and fewer reports back to Washington, both because his illness made him weak and because he simply wasn’t able to gather information anymore. Concerned about the drop-off in notes, Pinkerton sent two agents to check on things. Unfortunately, these agents were caught and put on trial for spying and treason. In order to save his own neck, one of them gave up the identity of Timothy and Hattie, leading to both of them getting arrested.

Timothy’s condition did not improve in prison. After a quick and unfair trial, he was sentenced to hang for treason. Hattie begged for his life, or at least for him to not be hanged like a common criminal, but her words fell on deaf ears. Timothy was hanged a few weeks after his trial in 1862 and the petition to allow his body to be buried in New York was denied.

Mary Touvestre

Mary Touvestre (sometimes referred to as Louvestre) was another former slave who risked her life spying behind Confederate lines. She posed as a seamstress and housekeeper for one of the Confederate naval engineers.

In 1861, the ironclad USS Merrimack was captured by Confederate soldiers despite Union attempts to destroy the grounded ship. The Merrimack was brought to Richmond, Virginia for repairs and restyling as the CSS Virginia. One of the engineers working on the ship was Mary’s employer. She overheard conversations about the plans to rebuild and fully outfit the ship with strong weapons, something that would be a strong threat to the Union. One night, she stole the blueprints for the ship, sewed them into her dress to hide them, and made the 190-mile trek to Washington on foot to deliver the news.

This spurred the Union on in their plans to build a new ironclad, speeding the process up by weeks if not months. As a result, when the Virginia hit the James river to clear the way for ships carrying supplies from Europe, the Union was ready with a blockade and a shiny new warship. Some historians speculate that the work of Mary Touvestre and Elizabeth Baker (who had also been in Richmond spying on new naval technology) may have shortened the war and possibly even impacted the outcome.

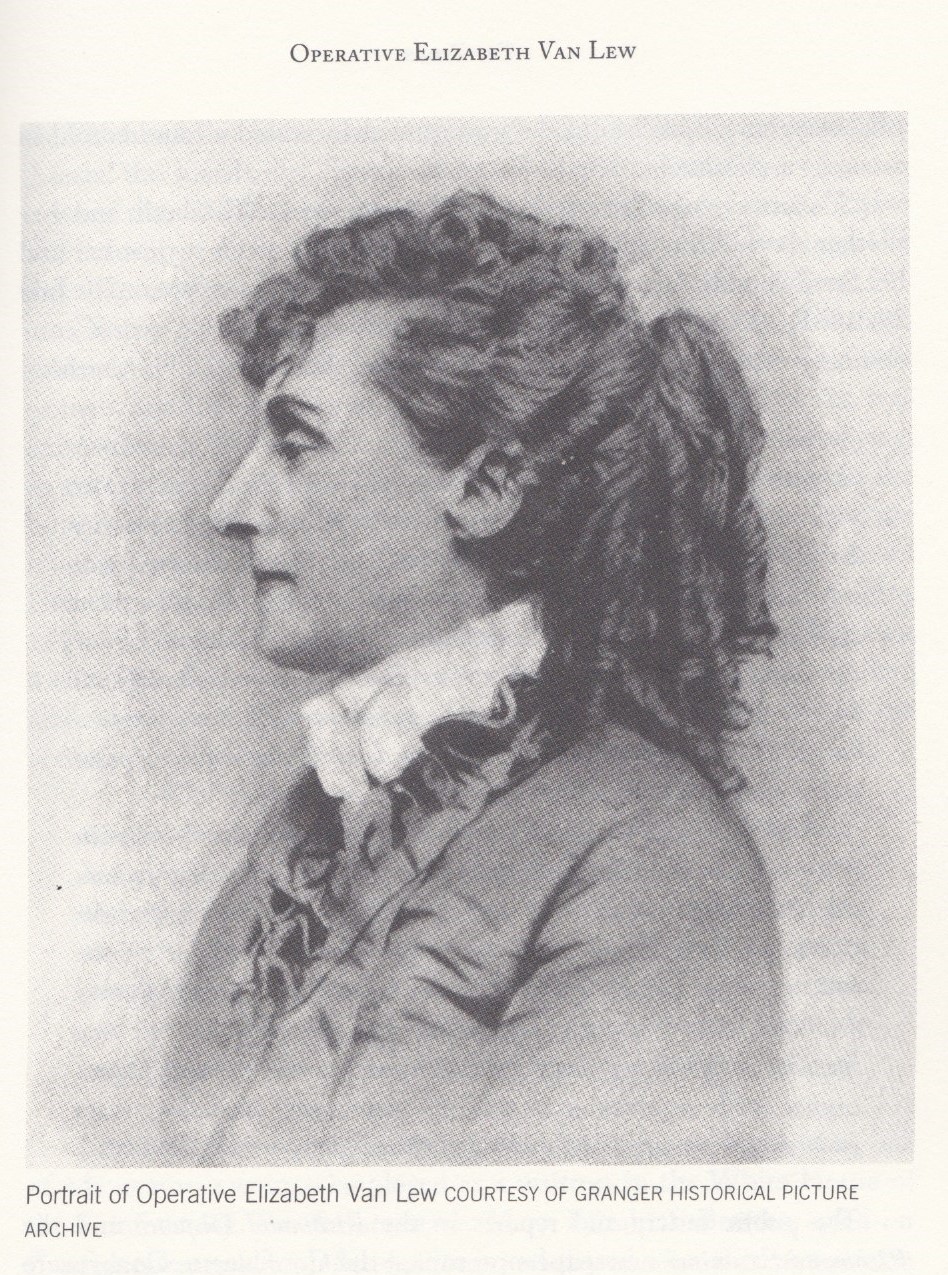

Elizabeth van Lew

Elizabeth van Lew came from a wealthy family in Richmond, Virginia. Unlike their neighbors, the van Lew’s were staunch abolitionists. Elizabeth’s father released his slaves long before the Civil War. As such, Elizabeth grew up with those same values and supported the Union throughout the Civil War. Part of that work was as a Pinkerton operative. She used her charity and mission work at the local federal prison (where many captured Union soldiers were held) to get information on Confederate troop encampment and missions to send out to Washington. She also had a contact in the Confederate white house that would pass information on to her. She also kept an eye out for Confederate female spies and even warned Washington that “All women ought to be kept from passing from Baltimore to Richmond. They can do a great deal of harm.” (Enss, 2017).

Though her work made her and her family a target for harassment in the local community and she fully believed that she would one day be found out and tried for treason, she soldiered on because she believed it was the right thing to do. She sent messages to Washington in any way she could, including hidden in egg baskets and shoe heels, and wrote in ciphers to prevent information leakage.

Following the war, her efforts were rewarded and she was appointed Postmaster of Richmond, something she was eternally grateful for as she’d spent all of her family fortune on supporting the Union during the war and needed the money to care for herself and her brother, a disabled former soldier. When President Hayes relieved her of her position in 1877 due to political pressure, she was able to get support from her friends in the North to keep her out of total poverty.

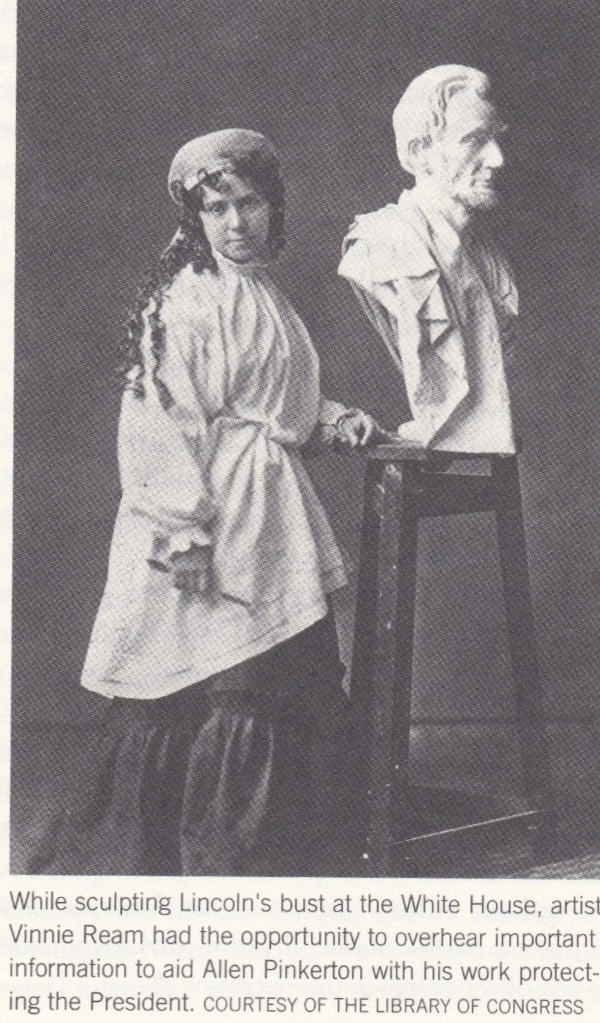

Vinnie Ream

Pinkerton believed that Abraham Lincoln may have people conspiring against him in his own party, so he arranged for a spy to be placed within the White House. For this position, he chose sculptor Vinnie Ream, who could use her position as an artist to blend in and listen for any anti-Union conspiracies and plots against the president. Prior to her work as a sculptor, she was employed with the USPS, making her one of the first women to work in the federal government.

Vinnie Ream kept her connection to Pinkerton secret her whole life, not even mentioning him or their work together in her memoirs. Despite this, some members of Lincoln’s cabinet became aware that she had some influence and tried to force her to use it for their gain. Their efforts went into high gear after Lincoln was assassinated and Andrew Johnson took over and they tried to pressure her into getting them votes for an impeachment. She was threatened with exile from Washington when she refused and was only saved by the efforts of her fellow sculptors.

[Portrait of Vinnie Ream, Courtesy of the Library of Congress]

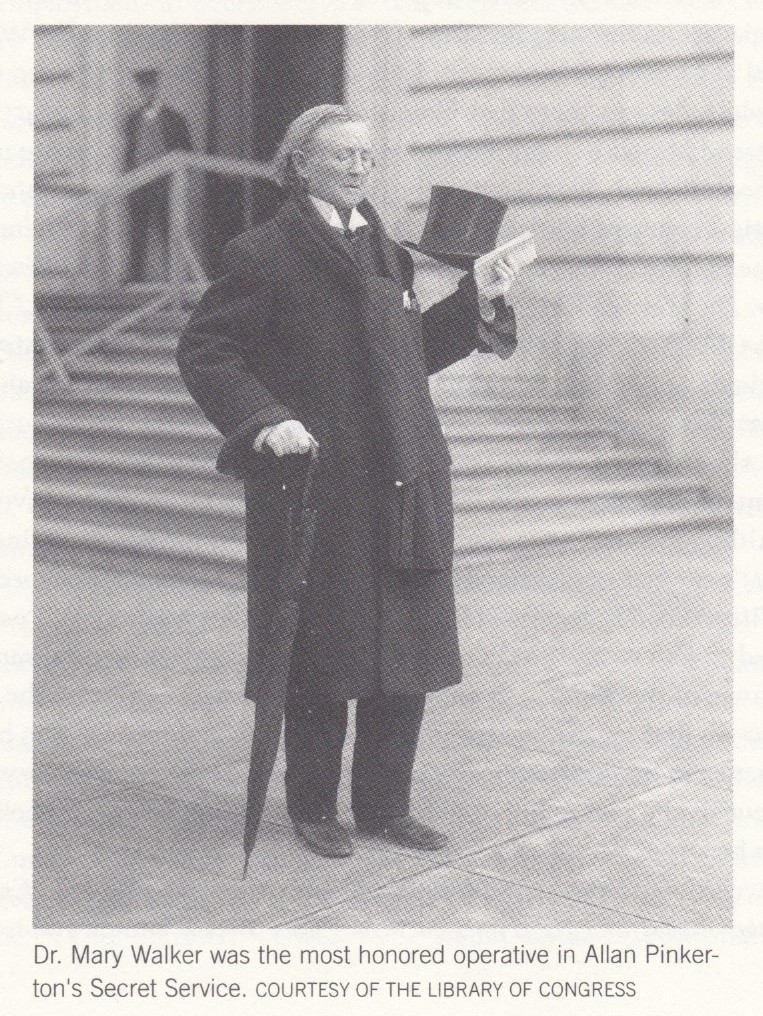

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker

Mary Walker was one of the first women in the United States to receive a Doctor of Medicine from a university. However, receiving the degree and technically having the ability to practice medicine did not mean she would be a success in doing so.

Her attempts to open a clinic with her husband fell apart with her marriage but she wasn’t going to give up. Shortly after the start of the war, Mary went to an Union enlistment office to offer her services as a field doctor. Despite the need for medical staff, she was denied a position. She was not deterred that easily and found herself working at several different volunteer hospitals that serviced both civilians and soldiers. She is noted as treating everyone with kindness and respect and doing everything she could with the resources she had available. It was while working at one of these hospitals that she met Allan Pinkerton.

Shortly after meeting him, she wrote a letter to Washington informing them that she would be performing spy duties on their behalf, going onto battlefields as a volunteer medic and crossing Confederate lines as a nurse to learn whatever she could. Anything she learned would be sent back to them in a cipher that Pinkerton could decode.

After a few months of her working as a spy, she was finally given the title of Major Surgeon and given a team of medics and soldiers to work with. The purpose of this was so that she could travel further behind Confederate lines and be captured in order to learn even more information. For four months, she was held captive behind enemy lines, learning all she could before she was rescued by Union soldiers.

Following the war, she was unable to find work. When she petitioned the Federal Pension Office for a small pension after her efforts during the war, citing her final title as Major Surgeon, she was told that she would not be receiving one because:

“Your appointment as the contract surgeon was made for the purpose, not of performing duties pertaining to such an office, but that you might be captured by the enemy to enable you to obtain information concerning their military affairs; in other words, you were to act in the role of a spy for the United States military authorities.” (Enss, 2017)

Despite the rejection, she kept writing letters in the hopes of getting some kind of compensation. In 1865, her efforts were rewarded, and she was given the Medal of Honor by President Andrew Johnson. She was the first woman to receive this award and the most decorated Pinkerton operative as a result.

52 years later, in 1917, she received a notice that, due to changes in requirements for the award, her Medal of Honor was being revoked and she, along with about 90 other recipients, were asked to return their medals. She refused to do so and proudly wore hers for the rest of her life.

[Picture of Dr. Mary Walker, courtesy of the Library of Congress]

Click *NEXT* for to Understand the Pinkerton’s Impact on the Walker: Independence Story!

Leave a Reply