Historical Context for Walker: Independence – Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency

The Pinkerton National Detective Agency, while not the first private detective force in America, is one of the more well-known. Pinkerton and his many operatives set the standard for private detective work, both in the real world and in the world of fiction. Though the agency was steeped in controversy from the very beginning, Pinkerton Inc. has survived 170 years and remains on the forefront of security and crime assessment to this day.

Today, I want to cover the history of the agency and see how the portrayal in Walker: Independence lines up with reality. I also want to talk about some prominent operatives that worked for the agency, especially the women, and see if there is any real-life inspiration for the character of Kate Carver.

Origins of the Pinkerton Agency

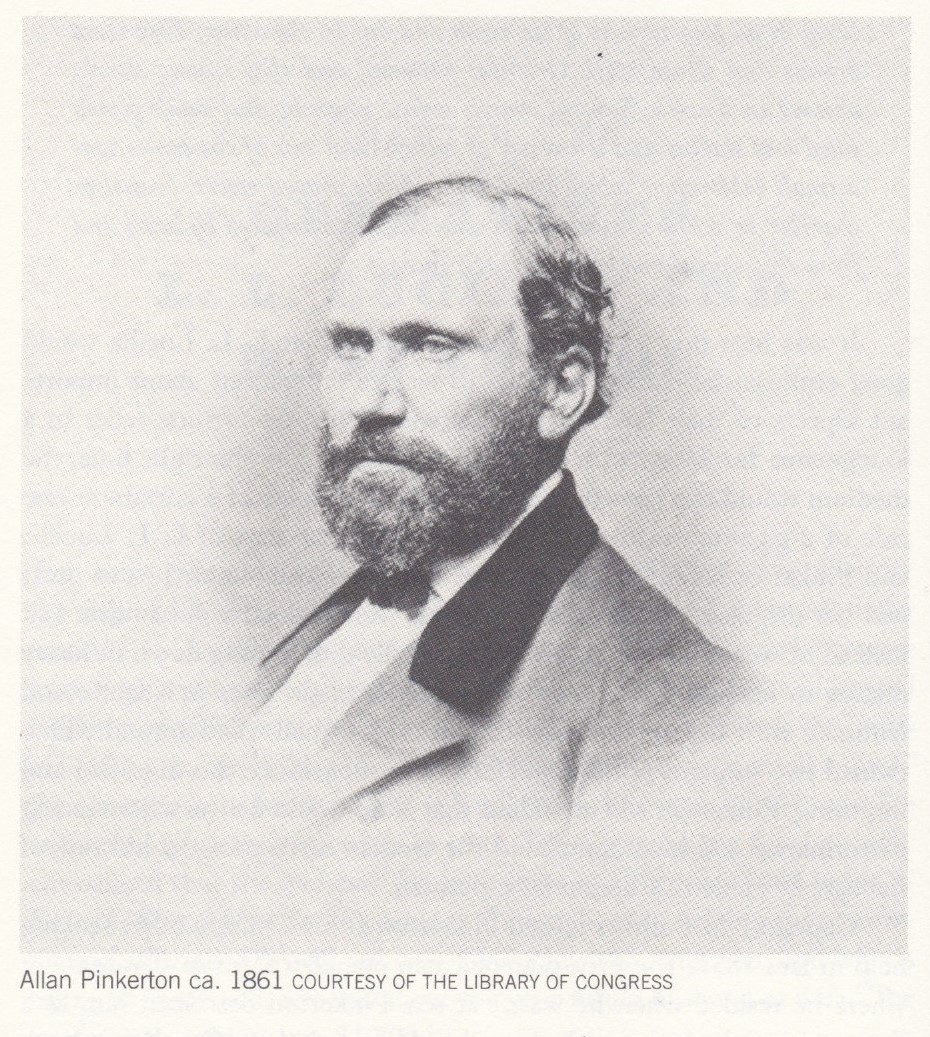

Allan Pinkerton started his work in law enforcement while living in his home country of Scotland. He wasn’t keen on the work, but his father needed someone to look after him and the work paid well. However, his outspoken political views on the rights of workers made him a target and, in the year 1842, he fled with his wife to the United States.

After a rough journey overseas during which they lost nearly everything due to a shipwreck, the Pinkertons landed in Canada and migrated south of the border to a small town outside of Chicago, Illinois called Dundee. There, Pinkerton opened an independent workshop and took on multiple apprentices while he and his wife focused on starting a family. He had no intention of entering law enforcement or dealing with crime in any way at first, but things changed when the world of crime hit his doorstep.

While there was a national currency in the US during this time, there were still many local bills and bank notes in the outer edges of the country and the territories. These local currencies were recognized as legal tender, but they were incredibly easy to counterfeit. When a gang of counterfeiters set up shop near Dundee, it didn’t cause any direct issues for Pinkerton, but it did hurt his suppliers and business partners. This was enough to spur him into action. He hunted the counterfeiters down, found their encampment, and brought the sheriff right to them the next day. This act of effective law enforcement (something the US hadn’t seen for quite some time) led the sheriff to offer him a position working part-time hunting down counterfeiters. Pinkerton was hesitant at first but agreed and soon became the bane of the existence of many a counterfeiter in the Midwest.

Pinkerton would’ve been content to remain working part time like that while maintaining his business in Dundee, but growing anti-abolitionist sentiment made him uncomfortable. Pinkerton was in favor of abolition and was very active on the Underground Railroad, helping runaway slaves cross the border into Canada to freedom, even in the 1840s. He was drawn to the more abolitionist-friendly city of Chicago, where he moved into law enforcement full time. Soon after, he was offered and took the position of Deputy of Kane County, a position that made him “the terror of cattle thieves, horse thieves, counterfeiters, and mail robbers all over the state” (2017, Enss).

His work catching counterfeiters and other such criminals caught the eyes of both private businesses and the federal government and he found himself with many requests for private contracts to catch criminals that the public police were not able to catch. Calling upon individuals in law enforcement to work privately was not uncommon as, during this time, there were no state or federal law enforcement agencies and city-level law enforcement was largely ineffective outside of the city limits.

Pinkerton took on these contracts and, after receiving regular business from them for some time, decided to leave county law enforcement and create his own private detective agency in Chicago, Illinois called the North West Police Agency in 1850. The name “Pinkerton” would not enter the agency name until 1858.

Pinkerton’s reputation working for the federal government, both solo and as a part of his agency, meant that he was in good standing with them as the country ramped up for a Civil War. When he discovered a plot to assassinate the president-elect Abraham Lincoln on his victory tour to Washington, his warnings were taken seriously. Not only were he and his agents personally entrusted with the safety of the president, but he was given the opportunity to start the Secret Service in Washington in 1861. Here, he was able to further prove the capabilities of himself and his agents as they infiltrated the Confederacy and brought back information on battle plans, troop movements, weapons development and more. They were even able to bring down Rose Greenhow, a notorious Confederate female spy who used her connections in Washington and in the Union army to gain and send information to the Confederacy.

During this time, Pinkerton would open more offices in Baltimore, New York, and later in Wisconsin. Thus began a 170-year legacy of crime fighting and surveillance ethics.

Business Practices

Though the Pinkerton National Detective Agency was doing decently before the war, the work done for the Secret Service and the president-elect Abraham Lincoln was a great boon for them, as well as a massive amount of publicity. The increase in business and employment were great for the agency and they had regular requests coming in, especially from the railroad industry.

As the railroads expanded west, they left the safety that came with the regular public police force. Not wanting to rely on the unreliable county authority, many railroad companies turned to Pinkerton both for guarding against railroad bandits to prevent theft and for testing the honesty of their employees to prevent embezzlement. However, as Pinkerton operatives had missions further and further away from home base, Pinkerton found himself dealing with many management and trust issues among his own agents.

Much like the railroads, Pinkerton had to trust his operatives to act in a manner befitting their employment. From the very early days of his agency, Pinkerton expected his operatives to act in a dignified manner, to be classy and well-mannered. He wanted them to be clever and subtle while doing their work. He needed them to be discreet and capable of memorizing details that could be notated in a full report after an event. But he could hardly keep an eye on his individual agents when they were miles away and he knew from experience dealing with embezzling conductors on the railroads that simply trusting his operatives to do the right thing wouldn’t cut it. It was time to implement some new management strategies.

From 1865-1875, Pinkerton shifted his focus away from detective work and into employee management. He started with publishing employee manuals for proper behavior on the job, starting with Special Rules and Instructions to be Observed in Testing Conductors after a string of his operatives got caught spying on trains. The idea was to give them a list of specific rules and guidelines to follow so that they could learn how to properly spy without getting caught. He would expand on that idea in 1867, with the release of General Principles of Pinkerton’s National Police Agency as a general policy book for all employees in all situations. This handbook would go over many revisions over the next few decades as times, policies, and ownership changed.

Pinkerton believed that “the profession of the detective is a high and honorable calling” (Morn, 1982) and he expected his operatives to uphold that standard. His expectations for operative behavior included (but was not limited to):

- Recording both favorable and negative facts and behavior around suspected individuals. All reports must be completely factual with “no endeavoring…to over-color or exaggerate anything against any particular individual, whatever the suspicion may be against him” (Morn, 1982)

- Operating within a small budget provided by the agency and send in a detailed expenditure report

- Reporting on what they did during their time off

- Prohibited from excessive drinking, even when off the clock

- Most importantly, keep their identities and work a secret. If an operative was discovered as being a private detective on the job, they were considered useless and a danger to the agency.

Violation of any of these rules would result in termination of employment.

In 1872, Pinkerton was forced to scale down and eventually remove the railroad employee testing program because more and more operatives were being caught spying and some secret offices had been found by railroad Union men. This, among other incidents (including one of their own getting caught embezzling agency funds), led Pinkerton to face the reality of the situation: his operatives were not going to follow the rules on their own. It became necessary to spy on the spies.

In 1874, Pinkerton adopted a policy of internal spying. He would not hire outside help to oversee the inner workings of his business but he did assign a few trusted individuals, mostly those within upper management that he’d worked with for many years, to spy on his operatives. For example, Mrs. Stanton (the head of the female department at the time) spied on their female operatives and reported directly back to Pinkerton on their activities.

But untrustworthy employees were only the beginning of Pinkerton’s problems.

Private Eyes in the Public Eye

Allan Pinkerton believed that he and his operatives were fulfilling a necessary service that the public police couldn’t provide. As true as that might be, not everyone agreed. Pinkerton had to spend just as much time proving his agency’s worth to the public as he did running his business.

Pinkerton was lucky in the early days of his business. While detectives did have a reputation for being just as bad- if not worse- than the criminals they captured, the public police force wasn’t held in high regard either. Many people viewed the mere existence of the police department as a form of government overreach and were more inclined to trust a similar force that was run as a private enterprise. Another reason people disliked the public police is, as I mentioned earlier, they were largely ineffective, and many considered them to be incompetent.

Prior to the 1840s, there were no public police in America. For the most part, individual citizens kept an eye out for crime during the day and a team of watchmen took over during the night. Most people would’ve been happy to keep this method going but the major population boom brought about by immigration (major cities like Boston got a 79% increase in population over 40 years) brought a crime surge with it. The usual methods just couldn’t keep up and New York brought the first city-level public police department into existence in 1844. In the coming years, other major cities followed their example.

These early police were a slight upgrade from the night watchmen. They worked during the day and they had the power to investigate and arrest suspicious individuals. However, they did not have any formal training or procedures, or even an official uniform until 1853. The uniforms were introduced as a way to hold the patrolmen accountable and prevent them from cowering behind their civilian clothes with inaction. While the public police did help deter crime, they also overloaded the justice system with increased arrests. Furthermore, the general public viewed them as an act of government overreach and treated them as mere puppets for whatever political powers were in place in the city (which was not entirely untrue).

On top of all this, the public police were only capable of acting within the city, leaving the areas outside the major metropolises lacking in ways to fight crime as there were no state police or federal institutions at the time. With all this in mind, it’s no wonder that people, from individual persons to businesses to the federal government themselves, turned to private law enforcement for aid. This dependence on private police to do what the public force could not is what helped Pinkerton thrive in the early years.

While business boomed during and after the Civil War, Pinkerton’s undercover operatives began to ruffle some feathers. While many people appreciated the hard work and courage displayed by Pinkerton operatives who crossed the Confederate border to spy on the rebels, they didn’t appreciate that the government continued to hire those operatives after the end of the war. There was no longer an enemy to fight and spy on and people didn’t like the idea of the government lying to them and invading their privacy (some things never change). Between this and the Pinkerton Police Patrol (patrolmen and guards for hire) being given the power to arrest citizens they caught committing crimes, people started to question whether or not a private business with no public accountability was the best way to cover the holes left behind by the public police. This is when things started to get rocky for the agency.

Despite criticism from both members of the general public and anti-detective lawmakers, Pinkerton made every effort to prove that detectives were trustworthy and that his detectives were more trustworthy than others. For example, he would not allow his operatives to take on cases that involved shadowing jurors or working for one political party against another. They would also reject cases that involved divorce or any other kind of public scandal. In order to avoid accusations of taking “blood money”, Pinkerton charged a flat rate for their operatives and would not take on any cases that involved reward money.

But all that effort would only go so far. More and more private detective agencies cropped up and some of them seemed all too happy to fit the brutish, underhanded detective stereotype. There were many detectives that seemed (from Pinkerton’s perspective at least) to be in the business purely for the sake of notoriety in the papers by being just as dastardly and underhanded as the criminals they chased after. There were also Divorce Detectives who specialized in trailing unfaithful spouses to gather evidence for divorce hearings.

The lack of accountability for private detectives is what got people most upset. Sure, the police were bad but at least they had a uniform you could identify. Private detectives got away with anonymity, which made some people uncomfortable, especially when they were carrying out government contracts.

While the actions of other detective agencies did reflect poorly on Pinkerton, the actions of their own agents caused a fair amount of distrust in their agency. I mentioned earlier that Pinkerton had to quit testing employees for dishonesty because they kept being found out. Pinkerton also regularly came under fire for their work stopping railroad bandits like the Jesse James gang. While railroads and many private citizens hailed them for their heroics in stopping bandits, there were just as many members of the public who supported the bandits. There were many outlaws who had gained the title of “social bandits” and were considered Robin Hood in comparison to the railroad executives and lawmen who chased them down.

One noteworthy scandal regarding Pinkerton and the Jesse James gang went down in 1874. During a confrontation with the gang, two Pinkerton agents had been killed. Pinkerton did not take this lightly and decided to work a little revenge into his justice. He wrote to a friend after this that if and when he found the gang again “it must be the death of one or both of us…my blood was spilt and they must repay” (Morn, 1982). Nine months passed and the James gang made a mockery of Pinkerton’s attempts to capture them. Then, on January 26, 1875, a group of Pinkerton agents surrounded the house on the James brothers’ mother’s home, following a rumor that they’d taken up residence there. One agent threw a fire bomb to see who was inside. The brothers were not there but the explosion from the bomb killed a small boy and severely wounded the mother. A pistol with the Pinkerton insignia was found by investigators afterward, tying the agency to the raid.

Not only did Pinkerton not deny that the raid happened, he never apologized for it. He firmly believed that what he did was justified. Naturally, the public did not take kindly to this and the reputation of the Pinkerton agency took a major hit.

But Pinkerton was already thinking of other ways to combat poor public image. If the newspapers wouldn’t provide him with the good publicity he needed, he’d just have to make it himself. So, from 1874 to 1884, he set about publishing detective novels featuring true events from the Pinkerton case files.

He published 16 novels in total, a feat he achieved by not actually writing the novels himself. Rather, he dictated anecdotes and incidents from case files to a stenographer, sent the transcript off to a real author, and made some edits to the final manuscript before publishing it for sale. His purpose with these books was not only to ride the popularity of detective novels at the time and gain the favor of the public, but also to correct the over glamorous perception of detective work portrayed in most detective novels.

For the most part, his plan worked. People ate up the Pinkerton novels and many appreciated the realistic look into the workings of detectives and the criminal underworld. However, these books ended up being a double-edged sword as some people questioned the methods used by the Pinkerton operatives.

Shortly after the publication of his last novel in 1884, Allan Pinkerton passed away, leaving his business to his two sons.

Evolution of the Pinkerton Agency

Allan Pinkerton’s sons, William and Robert Pinkerton both had a mind for the work, but they had different ideas on how to run the business. William had become a rather successful detective in his own right, earning him the moniker of “The Eye” in criminal circles, and he believed that the detecting side of the business was the most important. Robert, on the other hand, had always had an eye on the possibilities of expansion, specifically in their private security sector. He decided to expand the Pinkerton Patrol into Union Control services. This included spying on Union meetings and reporting back to the bosses, sending patrol men to control strike crowds, and even sending men in as strikebreakers. The one thing they agreed on was that women were no longer needed (they, like many outside the agency, believed the mere existence of female agents was proof of their father having an affair) and female operatives soon completely disappeared from employment records.

Business continued as usual, barring a few scandals regarding their work against workers unions. But with the passage of time came progress and by the early 20th century, police reforms and advances in technology meant that the detective side of the Pinkerton agency was becoming obsolete. William tried to maintain it as long as possible but Robert’s son, Allan Pinkerton II, saw that there was no future in it. By the 1930s, he had transformed the Pinkerton National Detective Agency into a private security firm that guarded property and persons.

That business model remains to this day and Pinkerton Incorporated has grown into a global company concerned with cybersecurity and crime risk assessment in countries around the world. Not bad for a company that started with rooting out counterfeiters and chasing train bandits.

Click *NEXT* to learn about the Most Notable Men and Women of the Pinkerton Agency

Leave a Reply