Historical Context for Walker: Independence – The Buffalo Soldiers

Introduction

When Philemon Chambers first mentioned that Augustus was once a Buffalo Soldier in an interview, I was intrigued. When we learned in “Random Acts” (1.06) of Walker: Independence that Augustus’ time in the Buffalo Soldiers was what led to him and Calian meeting and becoming friends, I was hooked and needed to learn more.

The Buffalo Soldiers were a sector of the US peacetime military following the Civil War made up entirely of black soldiers. Though slavery had officially ended during the war, equality and peace were still a long way off and many newly freed men saw joining the military as a way to make economic and social gains. These men, like many before them and even more in the generations to come, would put their lives on the line for their country in the hopes of being granted true equality and acceptance among the American people, a promise that would be made (and broken) time and time again.

I want to spend a little time talking about these men and the impact African American soldiers have had on US history. I’m going to do an overview of black soldiers in the military, which historians have traced back to the days of the American Revolution. I’m also going to do a more in-depth look at the origins of the Buffalo Soldiers and their time defending the American frontier. Then, I want to spend some time discussing how all of this could fit into the story Walker: Independence.

Before the Buffalo Soldiers

Traditionally, black soldiers were not allowed to enter military forces. It was believed that they would be cowardly, wouldn’t understand proper military functions, and would generally be a hindrance to the units they served. Despite that, during times of conflict, slaves would often try to volunteer in the hopes of gaining freedom. Typically, their pleas went unanswered until the situation on the battlefield was so dire that they feared they may lose. Even then, these men were usually relegated to labor positions and rarely allowed to carry a gun. Even if their freedom was promised in exchange for service, they would often be returned directly to their masters. This was a pattern that continued from times of colonial defense to the American Revolution and all the way through the War of 1812.

Then, the Civil War came along, and things shifted drastically for the US military.

Contrary to what some may believe, the slaves did not sit around twiddling their thumbs, waiting for freedom and equal rights to come their way during the Civil War era. Far from it.

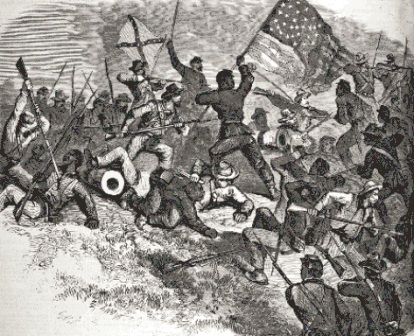

[Artist rendition of the Louisiana Native Guard (a battalion of black men) in battle for the Union, courtesy of Harper’s Weekly]

From the beginning of the war, slaves and freedmen both volunteered to fight in the Union army and shed their blood for their country and their freedom. Frederick Douglass advocated for them to join, believing that this would be a chance for them to prove their worth as humans and Americans. Even in the heart of the Confederacy, hundreds of freedmen went to enlistment posts to volunteer their services, likely hoping to leverage freedom for their still enslaved friends and family. After some struggle, these men were allowed to serve in combat roles on both sides, showing their passion and bravery through their sacrifices on the field. (For more information about African American soldiers on both sides of the Civil War, check out this article!)

Following the war, the black soldiers finally had their freedom but equal rights were not guaranteed just yet. But, with African Americans being allowed to serve in the peacetime army for the first time in US history, change was on the horizon.

The Buffalo Soldiers in Texas

Origins

Following the Civil War, African American soldiers were allowed to be part of the peacetime army for the first time in US military history. Many of them chose to do so as there was little chance of fair employment anywhere else at the time. While some of these men were holdovers from the Civil War forces, there were many more fresh enlistments. It was a good thing too, because the United States had a new enemy to combat: the Frontier.

The Buffalo Soldiers got their name not from the US army but from the Native Americans with whom they clashed. While historians argue over the specific origins (Cheyenne or Comanche) or the reason behind it (respect for the noble buffalo or a comparison in skin tone), they agree that the name originated from there in the early 1870s. Buffalo Soldiers was never an official title within the US military but the Soldiers adopted the title regardless and the buffalo imagery worked its way into their symbols.

While black and white soldiers alike entered the frontier, the main contributors to frontier advancement and safety were the Buffalo Soldiers who served on the plains from 1869 to 1889. Thousands of men served on the frontier during this time, but by and large the troops who had the largest impact on taming the land, especially in Texas, were the 9th and 10th cavalries of the Buffalo Soldiers. I want to talk about the work they did, the hardships they endured, and the impact they had on US and Texas history.

Life on the Frontier

Working on the frontier was no easy feat. The Buffalo Soldiers were expected to handle many different tasks aside from their primary objective of protecting the settlers on the far reaches of the frontier. Soldiers were expected to scout unexplored areas and provide information to map the frontier and find new Native encampments to keep an eye on. They were expected to protect both white settlers in the area and the Civilized Tribes (five tribes- Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole- who had made economic ties with America and/or had started cultural assimilation) from hostile Natives and track down any attackers. They were also expected to help local law enforcement against the Natives and the white criminals who took advantage of lax law enforcement out in the West. From cattle thieves to train robbers, the Soldiers were kept on their toes. As America moved West, they were expected to help with constructing and maintaining new forts and roads and to protect new railway construction. Delivering mail in this area was so dangerous and life-threatening that no white man would dare volunteer for the position, so Buffalo Soldiers were often required to handle that too, or at the very least escort shipments of supplies and money. It was harsh and thankless work but there was no one else willing to do it, so the Buffalo Soldiers did it.

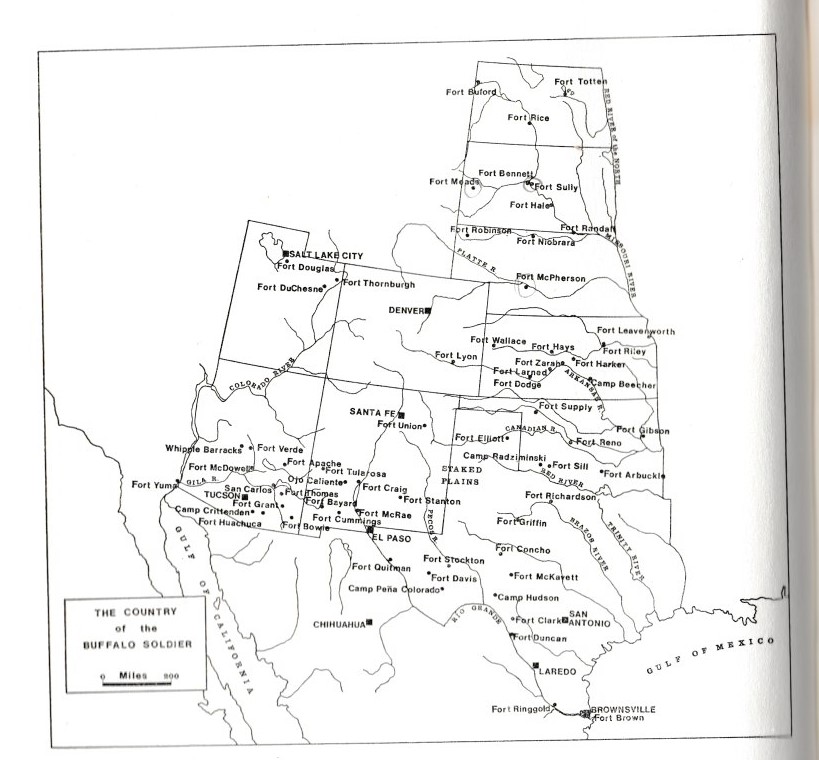

[Map representing the area covered by Buffalo Soldiers, Courtesy of the National Archives]

Cries for additional manpower and resources came from both individual Buffalo Soldiers and commanding officers, but the high-ranking officials in Washington (mostly men who had never been to the frontier) believed that conditions couldn’t possibly be that bad and denied their request every time.

The frontier was a massive area. From the Rio Grande to the south to Colorado in the north, there was a lot of ground to cover and not nearly enough men to do it. On top of that, it was a dangerous environment with harsh weather conditions and dangerous wild animals that didn’t like humans encroaching on their turf any more than the Native Americans liked the white man encroaching on theirs. The soldiers’ isolation from society made disease and injuries a threat as well, as disease could spread very quickly within encampments and needed medical attention could be miles away.

There were plenty of human dangers, too, and not just from Native Americans. Mexican revolutionaries in the border states and Kickapoos from the other side of the river posed a threat to the Buffalo Soldiers and settlers alike. Outlaws also made a home on the lawless plains and stirred up trouble for just about everybody There were also plenty of southerners who didn’t appreciate black men in the Union blue running around their territory.

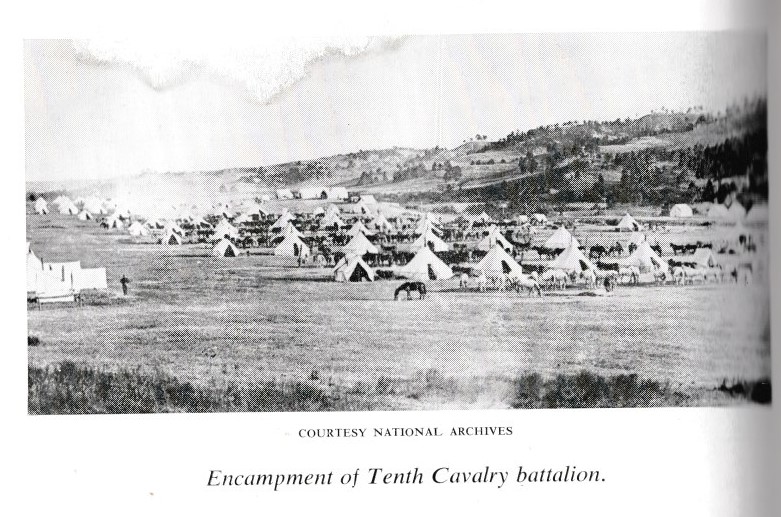

The long and short of it was that working the frontier was a very isolating and dangerous job. Many Buffalo Soldiers went months if not years without seeing their families and there was very little in the way of communication back to their homes. There weren’t many options for recreation either; settlements did pop up around their forts and encampments, but Buffalo Soldiers weren’t welcome in town and could very easily end up in trouble with the law or with the average citizen.

Then there was the matter of racism within the military. Punishments inflicted on Buffalo Soldiers for breaking the rules were often much harsher than those given to their white counterparts for similar infractions. The living conditions for Buffalo Soldiers were also much lower in quality than those given to white regiments. They were given poor food rations with near-spoiled bread and meats and none of the staples that could be found at a white encampment like jams and jellies or salt. Buffalo Soldiers were also paid less and had a harder time receiving recognition for their efforts; often the white commanding officers would be commended for their victories and the soldiers efforts ignored and swept under the rug.

Despite all that, the Buffalo Soldiers served their roles to the best of their ability and laid the foundations that helped build the American West.

The 9th Cavalry

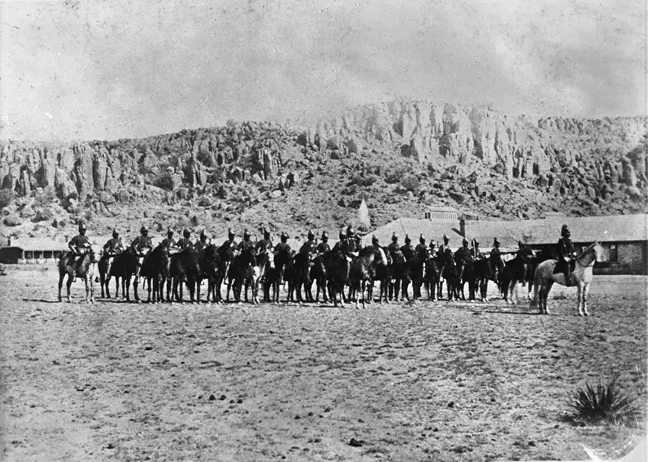

[9th Cavalry soldiers in dress uniform at Fort Davis, Texas, Courtesy of the National Park Service]

In February of 1867, Colonel Edward Hatch, the leader of the 9th cavalry, had put together a sizable cavalry of just over 1000 men. However, properly training them was difficult as he lacked enough commanding officers to oversee them. Despite the success of African American soldiers in the Union Army during the Civil War, many people had a hard time accepting that they were capable of being good soldiers and not even the offer of a promotion could get past the racism. But, when the orders came in to move to the Texas frontier, Hatch had no choice but to move his ragtag cavalry of barely trained men westward.

While doing operations in Texas, the 9th Cavalry was spread out across over 600 miles of territory between 7 scattered forts. As mentioned above, these men had a lot of territory to cover, a lot of responsibilities to tend to that no one else would, and not nearly enough men to do it.

After a few years working in this region, Hatch saw a way to decrease the workload for his men, at least in regard to the Native American threat. He saw how the Natives would attack in quick “hit and run” style robberies that would only serve to scatter the Buffalo Soldiers forces as they tried to chase the thieves down. He believed that he could decrease the threat if they could simply scout out where the Natives were camped out and make offensive attacks. His first attempt at a plan like this was in the spring of 1868, but he was moved out before he could enact it and his successor, despite being eager to go through with the plans, was faced with a summer full of quick hit and run attacks and battles that left the 9th scattered across the Texas plains and he didn’t have the time or manpower to do it.

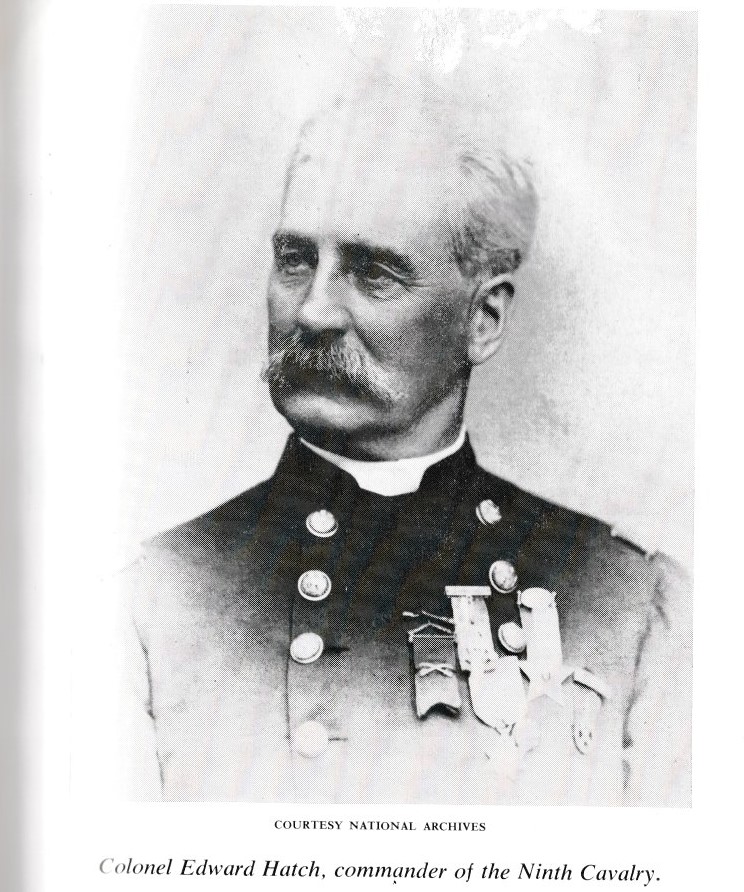

[Portrait of Colonel Edward Hatch, courtesy of the National Archives]

Hatch returned to his post at the 9th in 1870, when attacks from the Lipans and Kickapoos from Mexico were on the rise while attacks from tribes in the US were slowly decreasing thanks to smaller scale offensive campaigns from the Buffalo Soldiers. Here, he hatched a second plan to attack the Natives at their home base. The only issue was that he needed permission from both the US and Mexican government to follow these Natives across the border. While the US had no issue giving that permission, the Mexican government refused. Unable to do anything against the tribes from Mexico, the 9th turned their efforts toward the White Sands region, where many American tribes were hiding.

In summer of 1871, a large campaign was launched to track down these “hostiles” (Leckie, 1967) and drive them out of Texas. It was a hard march for the soldiers under scorching heat and barren landscape. For two months, they marched and scouted the land until they were too exhausted and too low on supplies to go any further, then they turned around and headed back to Fort Davis to recover.

Though this march initially seemed a failure as they had little interaction or success against the Natives, it did serve to be useful for mapping the region and preparing it for future settlers. The Buffalo Soldiers were also able to find evidence that the Sands were a common place for the Comancheros to trade. This campaign also helped to dispel the myth that the Buffalo Soldiers wouldn’t be able to survive in such harsh conditions, which rattled the Natives that had hidden away in what they thought was a safe place.

For years, the 9th Cavalry battled against harsh weather conditions, hostile Natives of all tribes, the disapproval of the post Civil-War, and uncooperative law enforcement officials. Though Hatch and his men were able to make a noticeable decrease in cattle thefts and took out a few bands of outlaws, the local law enforcement didn’t appreciate their involvement and took to blaming the Buffalo Soldiers for anything they thought they could get away with. This became so common that, in 1875, the US Secretary of War William Kelknap informed Governor Coke that, if this harassment against the Buffalo Soldiers didn’t stop, the federal troops and their support against the Natives and outlaws would be removed from the problematic localities. To prove his point, he ordered Hatch to move the headquarters of the 9th to Fort Clark and to take any outlying companies with him. This turned out to be a prequel to removing the 9th from Texas altogether a few months later.

Then, it would be the 10th’s turn to look after the Texas frontier.

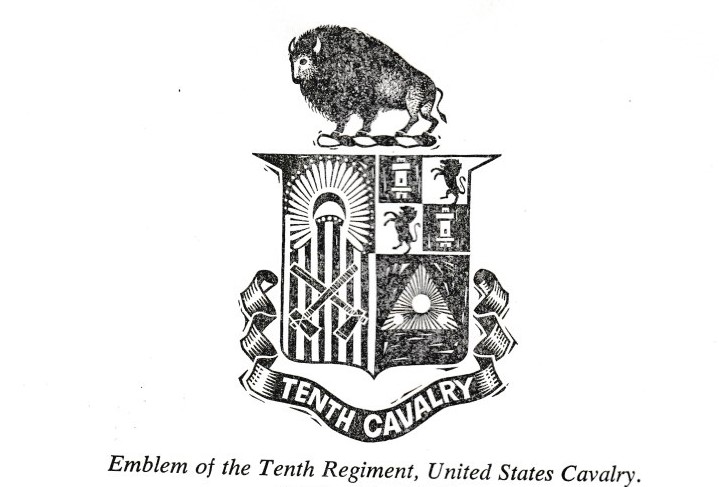

The 10th Cavalry

[Emblem of the 10th Cavalry, Courtesy of the National Archives]

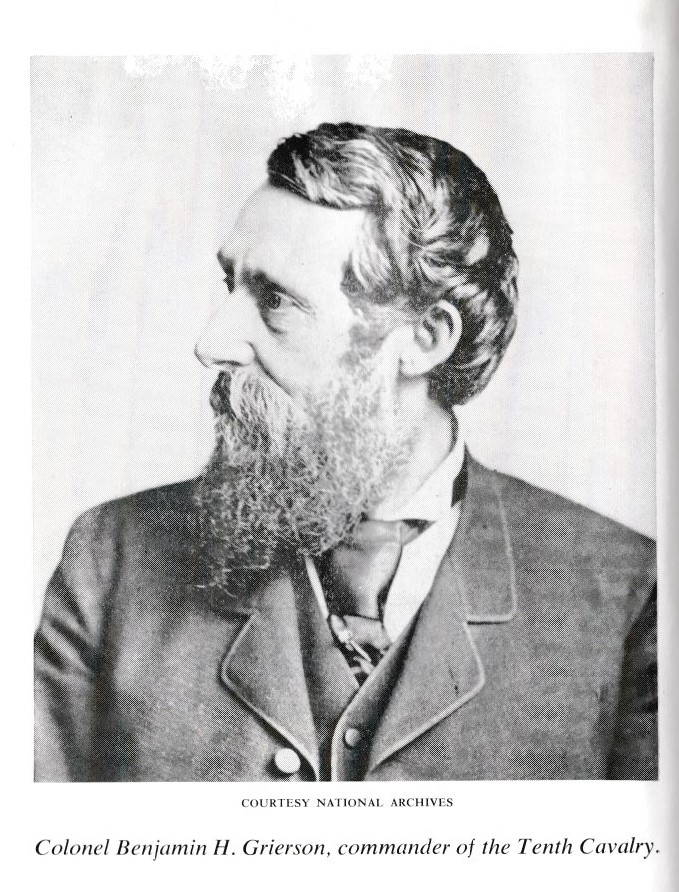

Like Hatch, Colonel Benjamin Grierson of the 10th cavalry had trouble finding commanding officers for his troops, but he also had issues finding recruits to train. Unlike Hatch, who recruited nearly any man who was willing, Grierson was looking for men who displayed intelligence and good physical composition among other qualities that he believed would make good soldiers. Pressure from Washington to move his men out West and the poor living conditions he and his men were forced into pushed him to increase his recruitment efforts. The 10th Cavalry set out on the trail to the Western Frontier shortly after the 9th. They spent their early years serving in Kansas and Indian Territory to protect the expanding railroads, but some individuals would move to Texas early to make up for the lack of federal presence to protect the more recent settlers. In 1875, following the Red River War, the entire unit would be moved to West Texas to help finish the work that the 9th had started in taming the west and the Natives who lived there.

[Portrait of Colonel Benjamin Grierson, Courtesy of the National Archives]

Things did not get off to a great start. When the 10th arrived, they had to deal with Comanches, Kickapoo, and Lipans harassing settlers along the Rio Grande, as well as bands of Mescalero and Warm Springs Apache further west. While Buffalo Soldiers ran themselves ragged handling the Natives’ hit and run attacks on farms and ranches, white outlaws and Mexican criminals were more than happy to take advantage of the distracted Buffalo Soldiers to take cattle and horses for themselves.

Much like the 9th, the 10th Cavalry found themselves dealing with the serious problem of not having enough men to cover all the (literal) ground and responsibilities they had to take care of, and, also much like the 9th, their pleas for reinforcements were ignored.

In May of 1875, General Ord had finally had enough of the hit and run raids and ordered a campaign to clear out the Staked Plains regions. Six companies of Buffalo Soldiers were included in this mission; the remainder of the 10th was preparing and guarding new railroad tracks and guarding the border from unwelcome Native raiders and Mexican revolutionaries. The purpose of the Stakes Plains Campaign was to scout out and map this largely unexplored region and expel any hostile Natives they came across. This campaign was difficult and lasted until November of 1875. It was a largely successful campaign as they were able to map the majority of the region and prepare it for new settlers and prove to the Natives that remained in the Staked Plains that it was no longer a safe haven for them.

[Photograph of an encampment of the Tenth Cavalry battalion, courtesy of the National Archives]

But this did not end Native troubles in Texas as there were still plenty of Lipans and Kickapoos coming up from Mexico. The Buffalo Soldiers still did not have the ability to follow them across the border, so any attempted interceptions of horse and cattle thefts usually ended in frustration and failure. But, for once, the US government listened to their soldiers and gave General Ord and his Buffalo Soldiers permission to cross the Mexican border to follow the “red phantoms” (Lecki, 1967) and put an end to the madness.

And cross the border, they did. From July to November of 1877, the 10th Cavalry ran campaigns south of border in which they followed the Native raiders back to their home tribes and attacked them on their own turf. They were able to kill a number of warriors, destroy encampments and supplies, and send a clear message to the tribes who made their home further south. They were even able to escape back to America without a single run-in with the Mexican Army (who weren’t exactly happy to have another country’s military on their turf). The only recorded death from this campaign was a single soldier who drowned while crossing the Rio Grande back into America.

Following this campaign, the Buffalo Soldiers were able to take a quick break and recuperate over the winter, but, as the only cavalry force in West Texas, they couldn’t rest for too long and were back in the saddle in January of 1877. Even with the decreased threat from below the border, there was still plenty of work to do, and now they had a new enemy: the Texas Rangers.

[A photo of some Frontier Battalion soldiers, courtesy of the Texas State Historical Association]

With many Native tribes moved onto the reservations, the US government was paying for buffalo to be hunted and arranging for the meat to be sent as food rations to these reservations. However, in 1877, the buffalo were nearing extinction, resulting in these rations being lowered and starving Native peoples. Native peoples begged to be allowed to leave the reservations in small hunting parties to find their own food and, after much negotiation, they were given permission to do so under supervision from the Buffalo Soldiers.

It should come as no surprise that the American citizens living in the areas these Natives hunted in weren’t exactly happy to see them running about with guns, supervised or not. Though there were no reports of cattle thefts or kills from these friendly hunting parties, fear and racial tensions caused an uproar among the settlers in Texas, an uproar that was loud enough to reach the ears of the Texas Frontier Battalion, a frontier defense force put together at the recommendation of Governor Coke in 1874. The Frontier Battalion sent a unit of Texas Rangers down to investigate the situation under orders to kill any armed Natives they saw.

Buffalo Soldiers often butted heads with these Texas Rangers as they had a habit of attacking peaceful Natives who were simply on a supervised hunting trip instead of the actual hostiles that still roamed the plains. Texas Rangers would argue that the Buffalo Soldiers weren’t doing a good enough job of supervising their charges and that they were just following their own orders. Disputes like this continued to happen until the 10th Cavalry was moved out of Texas just before the 1880s.

Though the 9th and 10th Cavalries didn’t get to witness the final taming of the frontier in Texas, they deserve a lot of credit for managing Native American activity and for scouting and mapping many previously unexplored areas so that they could be prepped for settlers. Though they may not have received much recognition for it at the time, or even after, their legacy lies in the civilized American west.

Beyond the frontier

After their time in Texas, the Buffalo Soldiers and other units of the US peacetime army continued their journey westward to tame and contain the remainder of the frontier. Coming toward the end of the 19th century and into the 20th, they were given a different calling: fighting wars against foreign forces.

Beginning with the Spanish-American War in 1898, Buffalo Soldiers and newer African American enlistments were called to the battlefield. They served well, as they always had, though they were largely used as support for the white units and rarely given battles and missions of their own until World War II. These soldiers, men and women alike, slowly worked their way into all the branches of the military during this time, though they remained in their own segregated units. Though there was talk of desegregating the military after witnessing the success of black units in Europe, many lawmakers and higher-ups in the military argued that racial tensions were just too strong to allow blacks and whites to work together.

President Truman forced the issue with an Executive Order in 1948 as the Cold War was on the horizon. Every branch of the military drug their feet over the issue and created mostly-black and mostly-white units within their forces, only desegregated in name rather than in spirit. It wasn’t until the Korean War in 1950 that the military saw true integration among their forces out of strategic necessity.

The Korean War proved to everyone that blacks and whites were perfectly capable of working alongside each other civilly, despite any lingering racial tensions. This paved the way for further civil rights legislation in the United States.

Buffalo Soldiers of Note

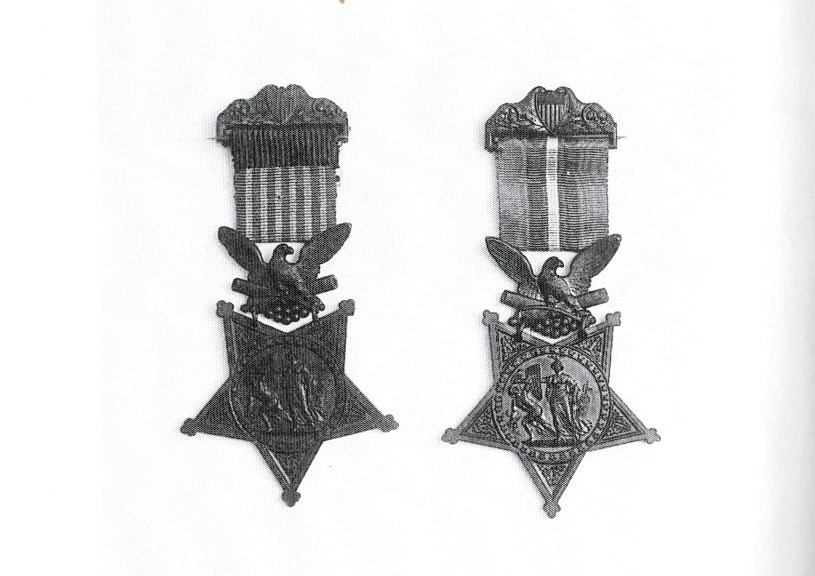

Though Buffalo Soldiers are largely ignored by historians and the current (and past) public consciousness, a good number of them did receive recognition for their valor and bravery on the battlefield. These men were awarded with the Medal of Honor, one of the highest military commendations at the time. The specific policy for a soldier to earn a Medal of Honor was “special and distinguished service in Indian warfare…some act of conspicuous bravery or service above the ordinary duty of a soldier” (Schubert, 2009). Over the course of the late 19th and early 20th century, 23 Buffalo Soldiers earned this award. I want to talk about some of those honored men here.

[Image of two Medals of Honor in two styles]

Emanuel Stance: Sergeant, F Troop 9th Cavalry- Texas Raid, 1870

Sergeant Emanual Stance was the first Buffalo Soldier to receive the Medal of Honor. Though he had a rough, bullheaded personality and was prone to drinking, he made a fine soldier and an excellent leader, often being tasked with leading one small detachment or another on scouting missions, or, the case he was awarded a medal for, a rescue mission.

In May of 1870, the step-children of Phillip Buckmeier were kidnapped by Apache raiders. Word was sent for help and two detachments of men, one of which was lead by Stance, went to Kickapoo Springs to search for and hopefully rescue the children.

Stance was the first one to spot the Apache raiders on the trail and he made the call to attack. There was a quick and dodgy battle that resulted in the Apache abandoning their horses and their precious cargo. The youngest of the children was rescued on the spot; the other, William, had been knocked from his horse when his Apache captors ran off and he hid until the fighting was over. The Buffalo Soldiers took the horses to an encampment in Kickapoo Springs to rest the horses and themselves and William made the trek on foot to join them.

When the rescue party returned, with 15 horses, two rescued children, and no injuries (aside from Stance’s horse), his commanding officer was impressed and recommended him for the Medal of Honor for this and previous encounters with Natives.

Adam Payne: Private, 24th Infantry- Comanche Campaign, 1874

Adam Payne was a Seminole Scout (a descendant of runaway slaves that found safety with the Seminole tribe and ran away to Mexico to escape the reservations in the 1830s; some felt safe enough to return to the US after the Civil War) that worked alongside the Buffalo Soldiers to help with tracking the Native Americans.

Payne was the first Seminole Scout to receive a medal of honor thanks to his efforts during the Red River War. The Red River War was an unusual alliance between the Comanches, Kiowa, Cheyenne, and Arapaho Natives against the American forces as a protest against the systematic killing off of buffalo herds and the failure of the US government to deliver on the promised food rations to their tribes.

Payne was part of a group of four scouts walking a few miles ahead of Colonel Mackenzie and a detachment of the 4th Cavalry on a trail along the Texas-New Mexico border. A group of approximately 25 Comanches saw them and attacked. Though they were outnumbered, Payne and his men fought valiantly and just barely managed to escape their attackers. They ran back to the 4th Cavalry’s encampment to warn them and started tracking the Comanches the next day. 6 days later, the men found a Kiowa and Comanche camp near Palo Duro Canyon near the Red River and attacked, destroying the camp and the Natives’ supplies, a rough blow just before winter.

Payne was among eight men involved in this battle who were recommended for the Medal of Honor. Colonel Mackenzie reported him “for gallantry…when attacked by a largely superior party of [Comanche]” and called him “a scout of great courage”.

Isaac Payne: Trumpeter, 24th Infantry; Pompey Factor: Private, 24th Infantry; John Ward: Sergeant, 24th Infantry- Staked Plains Expedition, 1875

Ward, Payne, and Factor all served on a recon mission with Lieutenant Bullis looking for Natives who had stolen 75 horses near the Pecos River Basin. They found the encampment within a few days of searching and, although they were only supposed to be doing reconnaissance, Bullis couldn’t resist the urge to engage with the Natives there. Bullis had them dismount and they slowly approached the encampment. Bullis fired the first shot from about 40 yards away, which turned out to be a mistake as not only did the Natives outnumber them, but they were armed with Winchester rifles.

For nearly an hour, the Buffalo Soldiers and the Natives were engaged in battle. Twice, the Buffalo Soldiers managed to chase the Natives back and secure the horses, and twice the Natives pushed back against them and recovered their stolen goods. Despite the difference in numbers, they were fairly evenly matched, but ultimately they needed to make a full retreat. Bullis was only able to escape by jumping onto Ward’s horse and the scouting group just managed to make it out with their lives.

Bullis recommended all of them for the Medal of Honor after this incident and all three of them received their awards within the year.

Clinton Greaves: Corporal, C Troop 9th Cavalry- Apache Campaign, 1877

The first Apache Campaign in the late 1870s was an attempt to move the Apache tribes to the reservations in San Carlos, New Mexico, a move that the Apache themselves did not agree with in the slightest and fought their hardest against. In late January of 1877, a group of Natives escaped the existing reservations in San Carlos and hid with the Chiricahua Apache in northern New Mexico. Lieutenant Henry Wright and his men were tasked with hunting them down and bringing everyone back with the aid of some Navajo Scouts.

When they found the encampment, Wright led six of his men, including Corporal Clinton Greaves, into the camp with the hope of negotiating the movement of all the Natives onto the reservation. However, as they went further and further into camp to speak with the chiefs, it became increasingly clear that negotiations were not on the table as they were strategically surrounded by warriors.

It should come as no surprise that fighting broke out and being surrounded and outnumbered was not a good situation for the Buffalo Soldiers. Greaves fired his carbine until it was emptied of ammunition, then he used his gun as a club to beat the warriors down. By doing this, he was able to create a hole in the circle of warriors and give his fellow soldiers a chance to escape.

[Image of a statue of Clinton Greaves]

Following this, Wright recommended Greaves and three other men for the Medal of Honor. However, due to some bureaucratic requirements not being met, Greaves was the only one to receive the award.

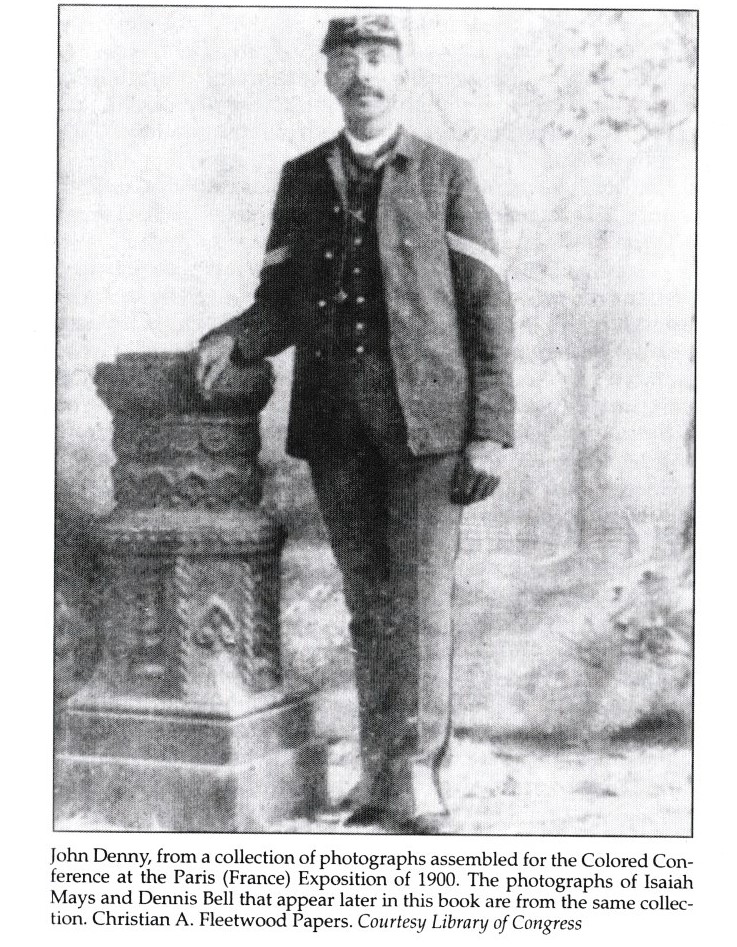

John Denny: Private, C Troop 9th Cavalry- Victorio Campaign, 1879

The Victorio Campaign was a military effort to take down Apache leader Victorio. Though there were plenty of peaceful Apache tribes already housed without reservations, approximately 6000 Apache still roamed the west in an expanse of land known as Apacheria, and they looked to Victorio for inspiration. He was considered to be the embodiment of “Apache resistance to white encroachment” (Shcubert, 2009).

During one of many confrontations with Victorio, Private John Denny proved his bravery and valor by aiding a wounded soldier. Under heavy fire from the Apache, he carried Private Freeland across the battlefield to a place where he could receive medical care. His commanding officer, Lieutenant Day, admired his unwillingness to leave his fellow man behind and it was later reported that Denny’s actions were “[an act] of most conspicuous gallantry” in the face of danger.

[Photograph of John Denny, courtesy of the Library of Congress]

Due to some bureaucratic oversight, Denny would not receive his Medal of Honor for this until 16 years later, but his tale of gallantry was still spoken of almost two decades later by the men of the 9th Cavalry.

William O. Wilson: Corporal, I Troop 9th Cavalry- Pine Ridge Campaign, 1890

Corporal Wilson’s ride to the Medal of Honor wasn’t as exciting as some of the other tales on this list but his work was just as important. He was the last Buffalo Soldier to win his Medal of Honor on American soil and the only one to desert his post afterward.

He received this award for volunteering to deliver a warning message from Lieutenant Powell to Major Henry, warning him of an ongoing Sioux attack on a supply train. This mission was dangerous as it would take him away from the safety of the wagon train and leave him alone in the harsh winter conditions of the frontier. None of the men in Lieutenant Powell’s troop would take the message and Wilson was the only one among his troop brave enough to take the risk.

So what does it all mean?

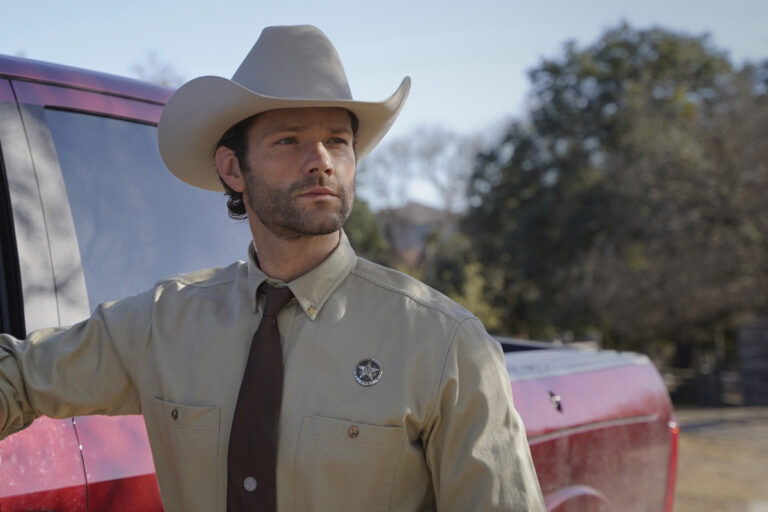

Now we’ve reached the part of the show where I talk about the impact that historical fact could have on the work of historical fiction known as Walker: Independence. It’s difficult for me to discuss historical accuracy as we have yet to see any Buffalo Soldiers in the show, but there’s still plenty of room to discuss Augustus’ background as a Buffalo Soldier and the potential future impact on the plot of the show.

Augustus’ Backstory

We know that Augustus was a member of the Buffalo Soldiers and that he spent at least some of that time working on the Texas frontier; this is how he met Calian, after all. So that tells us he was either a member of the 9th or 10th cavalry. I’m leaning towards the 9th as they had more responsibilities near where Walker: Independence takes place but, given all the (literal) ground that Buffalo Soldiers were required to cover as part of their basic duties, he could’ve been officially stationed somewhere else and just been sent on a mission to this area, so it’s hard to say for sure.

Next, let’s talk about how Calian and Augustus met. We know that Calian took Gus back to his camp to heal when he was injured, and that Gus decided to stick around after he had healed. What we don’t know for sure is how Augustus got this injury. Given the various number of tasks Buffalo Soldiers were required to handle and the mountain of dangers that came along with their station, there’s a nearly unlimited number of possibilities. I do have to say that I think the least likely cause of this was a confrontation between Calian’s tribe and Buffalo Soldiers.

[Image of Augustus and Calian, courtesy of the CW]

Though the Buffalo Soldiers were mainly on the frontier to keep the Natives at bay, actual confrontation between the groups wasn’t that common (at least not before the Natives were being rounded up for the reservations) given how spaced out the Soldiers were required to be. On top of that, most confrontations ended with the Natives being untraceable or just running across the Mexican border. On the occasions that violent confrontations did happen, there are no records that indicate injured soldiers would’ve been left behind, nor that the Natives would’ve made the effort to take care of them.

Based on that information, it’s more likely that Augustus was injured in some other way and Calian came across him on a scouting mission. As to the source of the injury, there are a lot of options there. It could’ve been a wild animal, a run-in with outlaws, or a hazardous mail run.

Though desertions among the Buffalo Soldiers weren’t common, it would’ve been easy to get away with one like Augustus did. The frontier was a dangerous place and there are many cases of men going missing only to turn up dead a week or so later. Even if it became known that he deserted, it’s unlikely there would’ve been spare time or resources to chase him. Augustus could have very easily ditched his blue uniform for a deputy star without getting in too much trouble.

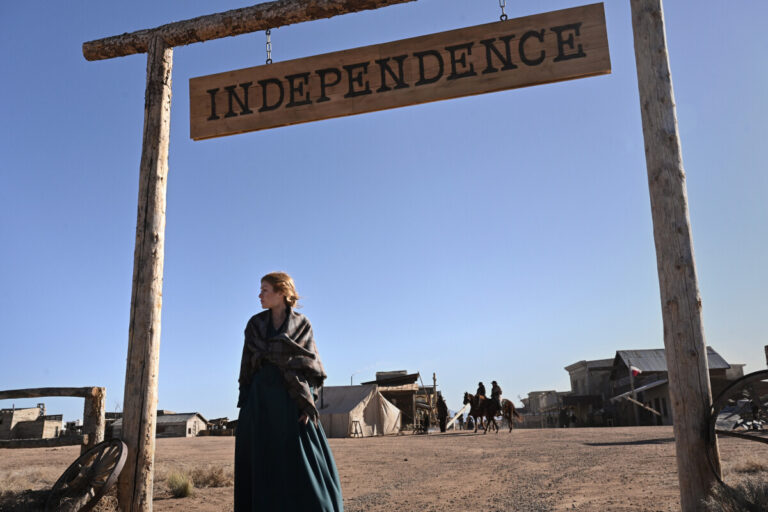

Buffalo Soldiers in Independence

Walker: Independence takes place during the beginning years of the Buffalo Soldiers and their war against the frontier. Against all logic, the Soldiers would’ve continued on without Augustus in their ranks. With a tribe of Apache next door, it’s likely that Independence would get a visit from them. Even without Calian’s tribe nearby, there are many reasons why Buffalo Soldiers would make an appearance in Independence.

The approaching railroad stop means that Buffalo Soldiers would be called to guard the railway from Natives and outlaws alike. Buffalo Soldiers were also tasked with doing mail runs all over the frontier, along with constructions projects for the government. They could come to town as a rest stop or to get supplies. Solders would also be asked to supplement current law enforcement so there’s room for a group of them to come in and step on Tom’s toes if it is decided that Independence needs help managing law enforcement.

With all that in mind, it’s likely that any Buffalo Soldiers we do meet could be a part of Augustus’ old regiment. Whether they would be friend or foe is another matter altogether.

Conclusion

The Buffalo Soldiers were brave volunteers who put their lives and sanities on the line for a country and a people who cared little for them. They helped lay the foundations in the West on which the country we know today was built and it’s a shame they didn’t get more recognition for it. While their impact on the United States is certain and recorded in various archived military documents, their impact on Walker: Independence remains to be seen. I, for one, can’t wait to see them represented on our small screens.

References

The Buffalo Soldiers: A narrative of the Negro Cavalry in the West, William Leckie, 1967

Civil War Special Forces: The Elite and Distinct Fighting Units of the Union and Confederate Armies, Robert P. Broadwater, 2014

Buffalo Soldiers: African American Troops in US forces, Ron Field, 2008

Black Valor: Buffalo Soldiers and the Medal of Honor, Frank Schubert, 2009

The Buffalo Soldiers: Their Epic Stories and Major Campaigns, Debra Scheffer PhD, 2015

Five Civilized Tribes: North American Indian Confederacy, The Editors of Encyclopedia Brittanica, March 2017. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Five-Civilized-Tribes

Frontier Battalion, The Texas State Historical Association, 1952. https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/frontier-battalion

Learn more about the historical period surrounding Walker: Independence! Dig into Dating in the 19th Century, Diversity during the Reconstruction Era, the US Civil War and Reconstruction Era, and the Evolution of Independence and Austin, Texas! Find them all in The WFB‘s History Tag!

Bookmark The WFB’s Walker Page and Walker: Independence Page for episode reviews, character analysis, historical context, spoilers and news!

Leave a Reply