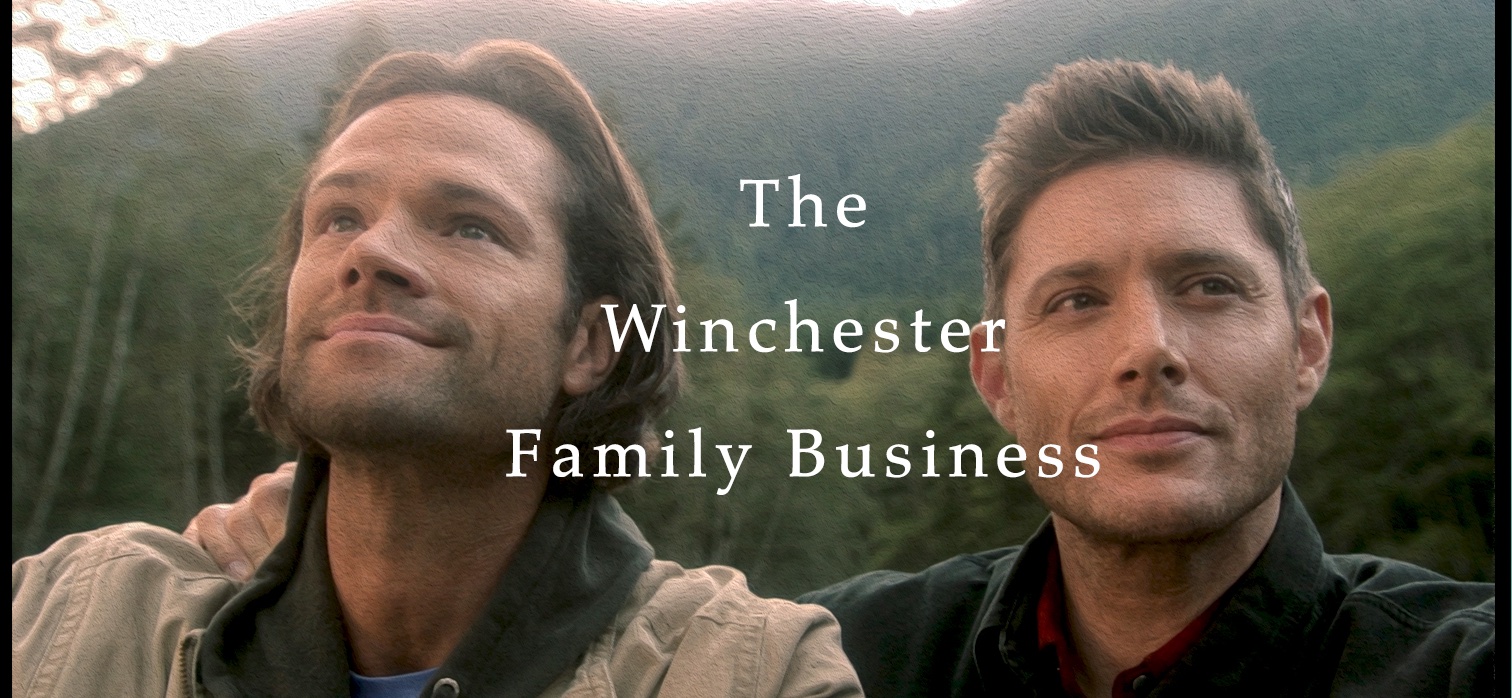

“How am I then a villain?”: Crowley as Supernatural’s Shakespearean Antagonist (Part One of Four)

Part One: Seasons Five and Six

“Cannot be ill, cannot be good.” – Macbeth, Act I, Scene 3

Villains and heroes share one important trait – they often act to build a better world, to right perceived wrongs, to bring justice to an unjust system. They diverge, many times, in motivation. Heroes tend to act from a place of common good, a common good that is shared by the audience, whereas the villain acts from a place of common good not shared by the audience. Good villains (and heroes) are not easy to create. There is always the danger of caricaturism, of creating one-dimensional personalities that speak words but are unconvincing in both action and motivation. Good villains are ambiguous – they require the audience to sympathize, perhaps even empathize, with their acts. One of the best writers of both heroes and villains was William Shakespeare, and this essay seeks to align some of Shakespeare’s most complicated villains with Supernatural’s most complicated villain, Crowley. I hope to delve into Crowley to show how he echoes a long line of valued antagonists, how he inherits and translates the villain for today’s genre audience.

There are many ways to read Shakespeare in the show, but in this essay I’d like to focus on how Crowley invokes the Bard through a well-constructed antagonism that provides a type of photographic negative to the heroes’ journey – a particular achievement that both the show and the playwright share.

Crowley allows the audience a way to read the Winchesters’ arc through its reactive effects. In other words, Crowley is his own hero in a competing narrative, but one that stands in contrast to the world the Winchesters are trying to save. By reading the show through Crowley, for a moment presuming him as our main character, I believe we can access parts of the narrative that may be foreclosed to us otherwise.

When I heard Mark Sheppard was being brought on as a series regular, I was excited. I would argue that Crowley represents a running thread in the Supernatural landscape – a very subtle gesture to an old influence, Shakespeare. And like Shakespeare, often the moral and weight of the story is carried by the antagonist – in this case, Crowley. In my opinion, Sheppard brings to the show a deep understanding of a flawed character and continuously combats bad parody to which a villain such as Crowley could be reduced.

Plain Dealing Demon

“….in this, though I cannot be said to

be a flattering honest man, it must not be denied

but I am a plain-dealing villain.” – Much Ado about Nothing, Act I, Scene 3

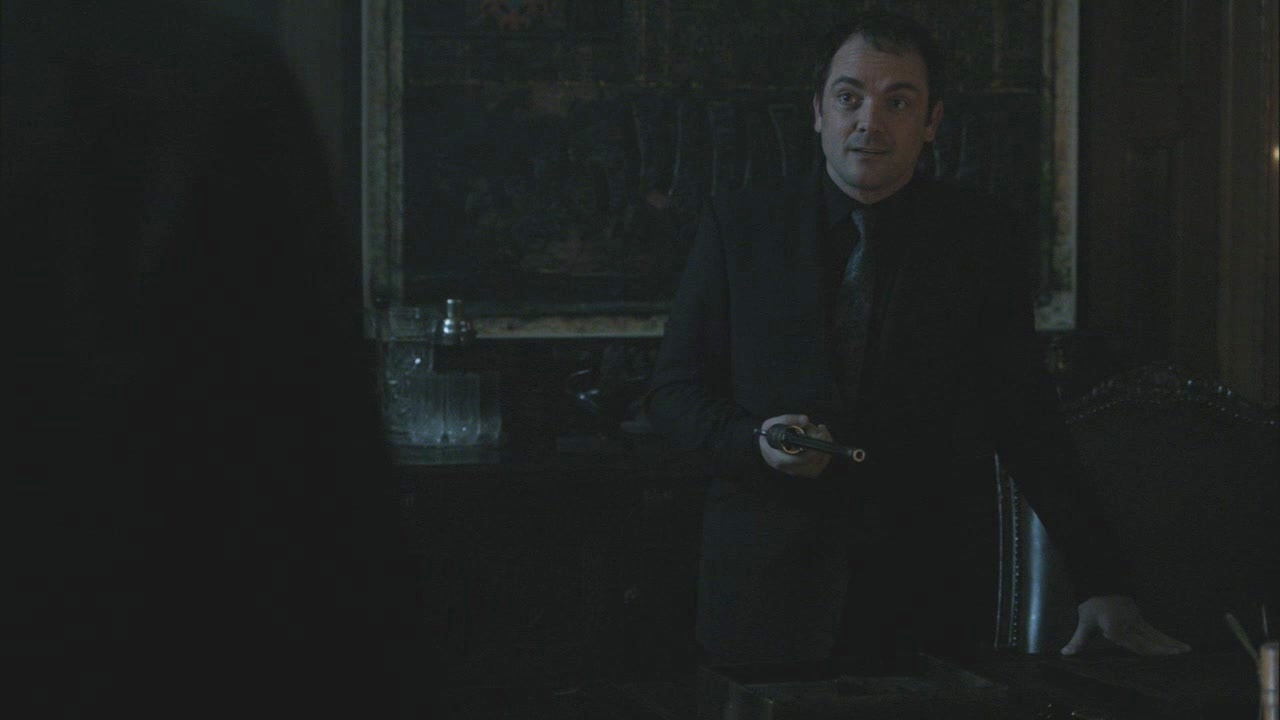

When Crowley first appears to the Winchesters in season five, he’s amassed wealth and privilege that is being threatened, so we see him as ambitious and territorial. He is an imperialist. In the battle against the angels, Crowley becomes an unholy ally and potential betrayer. The show does not mistake or misrepresent his motivation – he wants to conquer hell and the defeat of Lucifer will achieve that goal. He will have no competition. His ambition and his ambiguity serve to remind the audience of the stakes – Castiel, for example, is a known quantity in season five for his is still a character emotionally aligned with the Winchesters. Castiel is another soldier-son, trained to fight for and with the father, as opposed to Crowley who appears in the narrative as a rogue or even orphaned demon.

As he cements his alliance with the Winchesters in season five, Crowley confronts the audience with the complicated network of motivations that will infiltrate the narrative for the next eight seasons. Crowley’s introduction, in my mind, set up the moral and ethical battles the show and its heroes would face as the narrative moved thematically from one centered on the mythological frame of fate versus free will (which is an ancient theme that Shakespeare himself confronted in numerous plays) to the more concrete political and social commentary the show would engage during seasons six through eleven, and into twelve.

At first, Crowley’s desires seem commercial at their base – he wants hell and he will entertain a variety of mergers to get it. As a crossroads demon, Crowley exposes the economy (much like Don John does in Much Ado about Nothing) of the narrative world. Don John, for example, represents the cost system of primogeniture (right of the first born to inherit) to which he has been submitted as an expense – the bastard child who shall always be hidden from a pure heritage.

Crowley, too, is a bastard or illegitimate prince; Lucifer’s presence and potential victory poses a threat to his dominion. The angel is a true blood, a rightful heir – both Michael and Lucifer are direct descendants of God’s line whereas Crowley is the bastard of a corrupt and polluted system – a demon made from demons made from demons and thus we can never know his exact claim and even then, the claim is illegitimate since Lucifer, who created the first demon, rebelled against the father and endangered the kingdom’s lineage.

I would also like to note that I find it incredibly interesting that the show sacrifices a bastard son in its season five finale as an almost intuitive nod to its own complicated and contradictory fantasy of pure blood.

Further, Crowley emerges from an exchange system – the crossroads deal – that reveals Supernatural’s spiritual economy. The show introduces this type of deal in season two and it becomes the narrative force for seasons three and four – but I would argue that the idea of the “deal” goes further back to a season one episode, “Faith.” Supernatural has a basic economic query – it acutely examines a simple question: what is the price of life?

“Faith” answers that question in a way that frames the entire show – the price of life is death. Sam saves Dean, but an innocent man dies. Although he is unaware of the deal, the reaper stands in as its figure – a pointed invocation of a cultural metonymy – a death dealer. And from then on, the deal and its various iterations become a foundational concept for the show’s emotional interactions. John saves Dean, but at the cost of his life. Dean saves Sam, etc. and so on. The show even retrofits its origin story of Mary’s death to accommodate the deal narrative.

But the show hides this theme from itself, choosing instead to focus on the more mythological ramifications (and also the deeply personal ones) of dealing in and with life. Fate and free will mask the blandness and almost insipid notion of the show’s marketplace. It is only with Crowley’s introduction, coincident to Lucifer’s physical manifestation, that we begin to see the underlying system – Crowley, from there on out, is tasked with demystifying the world. And as a good antagonist, his role becomes apparent. His worldview counters the prevailing one of the narrative while at the same time divulging its price. But even at the end of season five, he remains in the shadow of the narrative. He heralds the change to come as the narrative of Supernatural moves from one that is mythological to one that is socioeconomic, which becomes apparent in seasons six and seven.

A Pound of Souls

“The pound of flesh, which I demand of him,

Is dearly bought; ’tis mine and I will have it.” – Merchant of Venice, Act IV, Scene 1

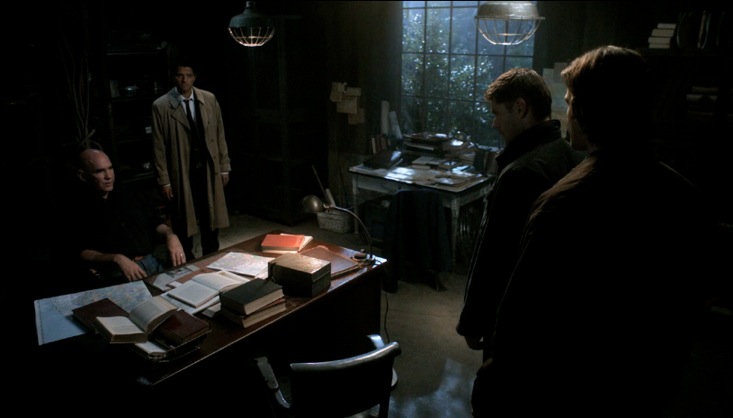

When Crowley reappears in season six he brings with him the cost of a saved world. He brings with him the price of life. Crowley holds onto Bobby’s soul, which he had bartered for cooperation in season five. He reveals himself as betrayer quickly – refusing to give Bobby’s soul back. The narrative, in this case, aligns with Castiel’s story. The rogue soldier or in Crowley’s case, the mid-level manager, now have the power that their initial betrayals had wrought. Castiel stands guard in a chaotic heaven while Crowley organizes his hell toward imperial profit.

As the Winchesters confront the reshaping of their relationships after the aborted apocalypse, Crowley invades the narrative, demanding the spoils of a now godless universe. Crowley’s story, though, challenges the Winchesters’ vision of family, which had been the “romance” story of the first testament, seasons one through five. Crowley’s schemes testify against this family romance by abrogating the Winchesters’ maternal inheritance. He enlists their grandfather, Samuel Campbell, in his imperial quest and as a result, he forever damages the Campbell line which is a part of the Winchesters’ origin story. Crowley’s greed, much like Shylock’s, calls for a fatal exchange.

It is an underlying irony that Crowley seeks purgatory, the place of spiritual purging and purification, as he seeks to corrupt both the Campbells and Castiel. This move opposes the Winchester narrative in season six, as it calls into question a loyalty presumed by blood and battle but also the purity of such fealty. Both Samuel and Castiel prioritize other familial connections over the Winchester brothers – for Samuel, his desire to rescue Mary from purgatory and for Castiel, his desire to rescue his brethren from Raphael’s seeming capricious rule. Crowley manipulates those desires and takes advantage. As a result, the Winchesters become tertiary figures in a story that had once featured them as primary agents.

I would argue that Crowley, Castiel, and yes, Death, all work to uncover the show’s economic ruin in season six. I would also argue that it’s not a coincidence that these narratives emerge in 2010-2011, at the height of the economic crisis in the United States. For so long the Winchesters had been protected from the cost of their actions. Their choices seemed isolated, even taking into account the “apocalypse,” because the story was concentrated on the brothers’ love for each other and the cost that love claimed – most notable in Bobby’s simple question in the penultimate episode of season five, “Are you worried about losing or losing your brother?”

The stakes change in season six and those changes are encapsulated, in my reading, in the Crowley character. He brings to bear the economic and social circumstances of the world, post apocalypse. The brothers are now situated in a larger social and cultural context – they move from being the saviors of the world to being merely participants and in fact are marginalized as the story becomes much more concerned with the politics and structures of previously (and currently I would say) mysterious realms, i.e. heaven and hell. The pound of flesh here, then, is the Winchesters.

As Crowley colonizes the narrative, he picks apart the world we had come to rely on but his colonization is the price of his cooperation in season five. And because he is a crossroads demon, his taking tally of the bill should not surprise us – so he helped the Winchesters save the world and now he requires that the Winchesters give up that world for his vision of it, and all of this capitalism occurs with the backdrop of souls as valuable possessions.

In the post season five apocalypse, the godless universe moves away from the soul as sentimental gift – where one offers one’s soul in exchange for another to a universe where souls can be harvested and collected, which also aligns quite nicely with the road narrative becoming less important. In other words the show’s economy moves from hunting and gathering to harvesting and collecting. And the show lays the groundwork for this transformation by beginning the season six story with a soulless Sam and furthers it with the seeming burning of Crowley’s bones – an act that has ramifications beyond the sixth season.

What had once been the prized possession of the narrative – a brother’s soul – now disappears from the story and must be reclaimed, but what happens thematically is that the soul is made explicitly extractable and disconnected from the actions of the soul keeper. Thus the soul is a prosthetic device and is no longer inherently attached to the body or the body’s actions. Furthermore the soul now contains an intrinsic value on its own – it provides power or fuel to the warlords, so in effect, the show strips heaven and hell of their masks, which had been an operating metaphor of hierarchy. There was God, then there were Lucifer and Michael, and then there were those who obeyed.

Of course much can be written about the show’s inability to commit to defining the boundaries of souls and their vessels, but in season six, the ability to extricate a soul becomes the economic bartering system. The ultimate death dealer, Death himself, reveals the power and value of souls as he sits with Dean at Bobby’s kitchen table. Death and Dean often fall into the Seventh Seal trope – the chess table image but here the food image, since it so clearly reflects Dean. Death appears as a refraction of Dean, a lover of junk food and sarcastic wit. In many ways, one could read Dean as Death and Death as Dean, which is why “Appointment in Samarra” is particularly poignant.

Once Death reveals the new social or natural order, Crowley’s plans for purgatory become more sinister and wide reaching. His alliance with Castiel is the keystone event that leads to the unraveling of alliances. He whispers poison in the ear of the potential heir, which invokes another dastardly villain, Iago. And while Crowley’s seeming desire to own, to conquer, to be king, presents as his most apparent character trait, it would be his anger, nay his rage, at the Winchesters that begins to uncover his more human nature. That rage emerges from an intricate set of emotions that foreshadows, to a degree, his place in the monument of saviors in the story. His capability to feel will position Crowley away from a refractive enemy, one that simply appears as the lens of “evil,” to a reflective nemesis, one who mirrors askew the demons which all good heroes must confront and conquer. It will be in season seven, though, when the Crowley arc swiftly moves from enigmatic enemy to complex opponent.

Part Two: Seasons Seven and Eight

The Spoiled Victor

Pictures Courtesy of The WFB Photo Gallery, http://www.homeofthenutty.com, and http://www.supernaturalwiki.com.

Leave a Reply