Far Away Eyes’ Deeper Look Supernatural 12.02 “Mamma Mia”

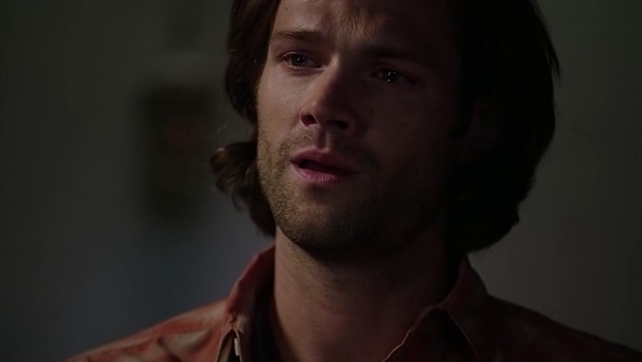

“If you ever wanna talk. I know what it’s like to come back and not feel like you really fit,” Sam tells his mother at the end of “Mamma Mia.” In many ways, the statement blankets the entire episode.

First, let’s look at the British Men of Letters.

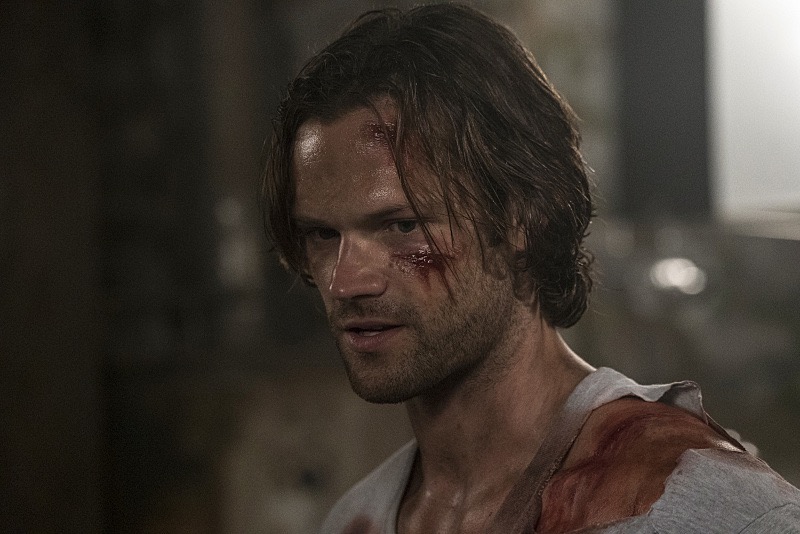

Lady Toni, in her quest to retrieve the names and locations of American hunters, has gone rogue. She has kidnapped Sam and tortured him in unspeakable and questionable ways. Having failed with pain, she attempts a more “pleasurable” but ultimately far more horrific method. Rather than break his body or his mind—she has chosen to violate him with a cruel spell. Her hallucinations yield some newer results—and yet still do not quite get her what she really wants. Sam still resolves to tell her “Screw yourself” as soon as he can break free of the spell work she’s used on him. She’ll have to resort to other methods—even without the likes of Ms. Watt.

The question of fitting in for the British Men of Letters isn’t about where they themselves fit in this landscape. It is a question about how the American hunters—and in particular Sam and Dean—fit into their scheme for the supernatural problem in America. Lady Toni sees them as the problem. She tells Sam her view on hunters, “They work for us. Tools. They kill. They don’t think.” She explains that they are there to do the job they’re given and nothing more. The concept of a hunter doing their own research or going from case to case on their own intuition is unheard of back home. In her estimation, it is why they’ve failed. She backs this statement up to Dean, telling him condescendingly, “You live in the Men of Letters Bunker, awash in the world’s collection of occult knowledge and yet you know nothing.” She sees Sam and Dean as nothing more than “apes”—the nice term she uses to their faces. Later, when she’s been apprehended by her superior, Mick, she tells him, “The Winchesters—these American hunters—they are no better than the monsters they fail to control. They need to be eliminated.” Clearly, in Lady Toni’s estimation, American hunters as they currently exist have no place in the reformed America she envisions—one that will see an end to the monsters and “worst nightmares.”

And yet, the problem they fail to see is that they, themselves, do not fit in the American hunting landscape. This failure may very well be the road to their undoing.

What of Lucifer? He’s stuck roaming from vessel to vessel, unable to really anchor himself—that is until he finds a vulnerable Vincent Vicente ripe for the taking. His attempt to “fit in” is merely to find that vessel that will work for more than a few short hours. Luring his victim in a similar fashion to how he once tried to trick Sam years ago, he appears to Vincent as his long dead girlfriend. The guilt Vincent feels about her suicide and his behavior towards her has ground his life to a halt. His bandmate begs him to live his own life. It’s too late, though. Vincent’s desperation makes it far too easy for him to say yes to the Devil, all without realizing that’s who he had let in.

Lucifer’s story links to Crowley and Rowena’s well. In the aftermath of the Darkness, Crowley has found his ambition back to rule Hell and Rowena has decided to hang it up and retire peacefully—or at least lie low for a few centuries and let the storms pass by. She’s schmoozing a man that seems well off and none the wiser to her true intentions. Crowley’s sudden appearance upends that apple cart and she hisses at him, “You’re like a boil that keeps coming back no matter how many times I have it lanced.”

In running to his mother, we see Crowley force her to debate a pertinent question: where do they fit in one another’s lives? He’s called upon her to put Lucifer back into the Cage—a feat that would benefit both certainly—but it leaves one to wonder with the animosity between the two why he chooses to run to her. They are family—rather they like it or not—and so they must find a way to fit into one another’s lives. As odd as it is for Crowley to run to his mother, however, it is far stranger to see Rowena acquiesce, given her hatred of her son. As he points out, her new boyfriend, “makes oatmeal look fascinating,” and thus strikes a nerve. Rowena thrives on intrigue and scandal and likes to be in the thick of things. She begrudgingly goes along with Crowley’s scheme—almost showing that their relationship has shifted since her poignant confession about hating him so not to love him. How they go about finding their place in their strange family and how they fit together and what it might mean is not resolved by episode end by any means. After all, Crowley’s scheme to have Rowena wrest Lucifer from his vessel and back into the Cage goes horribly awry—and the King of Hell teleports away to leave his mother in Lucifer’s brutal hands.

The question of fitting in, however, truly takes center stage when we examine the Winchesters. Each of them, Mary, Dean, and Sam must all assess where they belong now. They must all try and find a place in the new family dynamic and how they’ll go forward as a group. For much of Sam and Dean’s lives, Mary was either a memory or a story. For much of their lives, she was someone they honored by doing the job of hunting. Now that she is back, they must figure out how to mesh past and present—or how to pit memories and dreams against reality.

For Mary, this is a difficult transition. Raised as a hunter, she managed to get out and have a family and find the “apple pie” life for a period. It brought her happiness and peace. She had a loving husband and children and didn’t have the specter of evil hanging over her head—until that fateful night. Mary knows what she did. She carries her own burden of guilt about the deal she made with Azazel. Being with Dean, during their search for Sam, she confesses her fears to her eldest. Not knowing the man Sam’s become or the feelings he has for his mother, she fears the worst. She tells Dean, “That yellow-eyed thing would never have come for him that night if I… I started all of this.”

It’s a dark and sorrowful moment. She may not even know the entire story yet—those conversations have not taken place yet and she hasn’t had all of those “blanks” filled in about the Apocalypse or Purgatory. Mary only knows that the deal she made with Azazel led to her sons being torn from her, her life ended, and theirs turned into the hunter’s life. She knows hunters and understands their prejudices and may fear that her youngest may harbor some ill will perhaps for what’s happened. She knows that she felt some resentment towards her own father for forcing her into the world of hunting—a profession she still clearly has a love/hate relationship with. She can imagine that her youngest son would feel some of those same things towards her—even if she wasn’t the one actively hunting and dragging him along for the ride.

Mary’s astonished, however, to find out that Sam had managed to do what she once had: gotten out. Dean tells her that he went to Stanford, that he had left it all behind. The fact that Sam’s now here strikes hurt into her heart. One of her boys had done it and somehow gotten pulled back in. Dean tells her, “When Dad disappeared, Sam and I looked around and something became very clear. The only thing we had in this world, the only thing besides this car, was each other.”

The statement may provide comfort to her. After all, this is about fitting in with one’s family on some level—and the motivation to do this for family runs strong. Their partnership may stand as a testament to the good work they do and the sons she’s now getting to know. The fact that Sam was also willing to give up his own “apple pie” life may also prove his ability to forgive. He chose family over going to school. He chose to help his brother find their missing father—and while Mary may not know that Sam’s girlfriend, Jessica, met the same fate she did, she knows that her son must have a great heart.

Mary wants to fit into this new world she’s been thrust back into. She’s not entirely happy that her sons ended up in the very life she sought to keep them safe from, but she isn’t going to run away from it, either. That becomes clearest when she overhears Dean telling Castiel that he doesn’t want to overwhelm her or that she should stay back in the Bunker or wait out by the car. She tells Dean, “You can keep me from driving, Dean—not from hunting.”

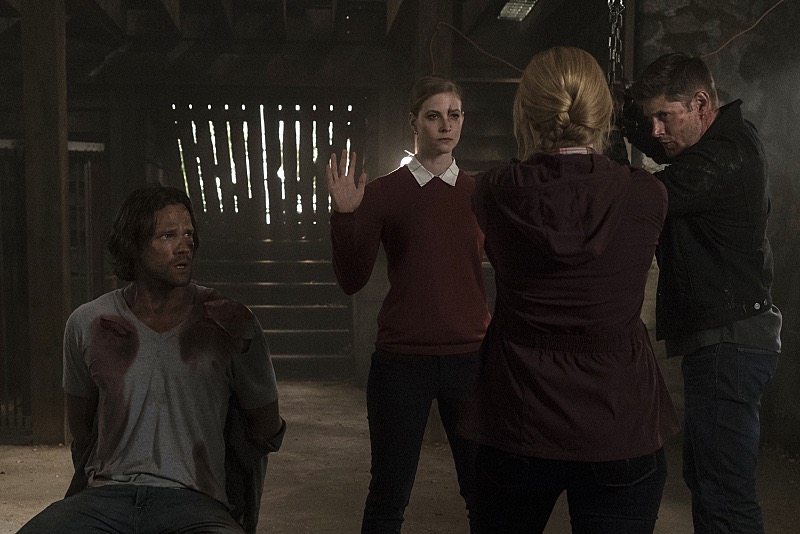

Their mother also proves her merit as a hunter while on the rescue mission for Sam. While she argues with Dean, she points out that she’s the last person they’d ever expect. Dean responds, “You were good at this, weren’t you?” Mary firmly and with pride replies, “Very.” Her actions clearly back up her words as she ignores the request to keep Castiel company and bursts into the scene just as Lady Toni begins to torture Dean. She shouts, “Get away from my boys!”

Quickly, it turns into a knock out fight, Mary insisting that Lady Toni get on the ground. When the command isn’t followed, Mary quickly punches the British Men of Letters in the face, telling her coldly, “That’s the ground.” Too soon, however, they end up punching and shooting at and kicking one another. Mary may not know her sons well yet, but they are her sons. She will not stand by and just let anyone hurt them—and she won’t just sit by the car while they’re in danger. She proves that her combat isn’t rusty and that she has no qualms about getting her hands dirty in the process.

Unfortunately, Lady Toni knows a spell or two that allows her get the upper hand and starts to choke Mary with magic alone. She is determined to disarm and capture all three Winchesters—and while Dean can’t kill her and risk his mother dying with the rogue British Men of Letters, he can disarm her little trick with a deft punch to the face. After all, it’s hard to use her “Chinese mind trick” when she’s unconscious.

In the aftermath of the rescue, Mary goes back home to the Bunker with her sons, enjoying the reunion and the quiet and comfortable time after the hunt. They eat a great dinner—and she watches her son eagerly dig into pie—while her other son is flabbergasted by Dean’s behavior. These are the moments that Mary will treasure in the aftermath of her resurrection. She may hate the life and hunting, but these are the very things that make it worthwhile—even if she misspeaks about “calling the Internet.” They are here, together, as a family. It’s all she’s ever wanted—mostly.

SeasonTwelve/12-02-Mamma-Mia/1202_SPN_1756

And, her earlier fear proves to be unfounded. Instead of being rejected or abhorred by her youngest son, Sam quietly and patiently states, “If you ever wanna talk. I know what it’s like to come back and not feel like you really fit.” He also can tell that his mother struggles with the loss of her husband—adrift in a way without the man she quit hunting for years ago. He hands her their father’s journal. When she questions why he came back to this—why he didn’t stay out of hunting when he had the chance, Sam reveals his heart to his mother—showing her the man he’s become and the son she’ll be proud to have. He says, “Well, this is my family. My family hunts, this is what we do.”

For Mary, now, she must question how she’ll fit into this family that hunts—and if she truly desires to leave it behind as she once did. After all, these are her sons and she wants to fit in with them.

Dean, too, has to navigate the new family dynamics his mother’s return brings. He has been focused on finding leads on Sam and on keeping his emotions under control for his mother’s sake—clearly evidenced in his conversation with Castiel. He doesn’t want to freak her out. He doesn’t know where to begin with her, and he doesn’t know how to relate to her entirely. He loves her and is thrilled to have her back—but at the same time, there’s a strangeness about having her back. It’s awkward at times and hard to bridge the gap between what he remembers and the reality that stands before him. He tells the angel, “It’s been kinda weird here with, you know, Mom being back. It’s like we don’t know how to act around each other so we just kinda make this small talk and act normal, but it’s so not normal.”

Unfortunately, his mother overhears and the “chick flick” moment that he’s avoided with his mother can no longer be put off. He has to face it rather he wants to or not. His mother remains stubborn about hunting—about helping him to save Sam. When Dean tries to tell her, “Why don’t I take this one solo, okay? We don’t know what we’re walking into here,” he’s revealing all of his anxiety. He builds on it by telling her “I can’t do my job if I’m worried about you.”

Dean wants Mary in his life badly, and he wants to fit her into their new family dynamic—and yet he’s struggling mightily with what it means for himself. How does he face a mother that’s been gone for 30 years? How does he handle the fact that she’s a tough and experienced hunter and yet removed from a time that did not have the Internet or the Apocalypse? His mother stirs emotions in him, too—one’s that Dean’s spent his entire life burying. After all, in the aftermath of her death, he’s been the trapped little four-year-old boy all this time to some degree. To have her back is to dredge up those memories.

His comment about being overwhelmed isn’t so much about her as it is about himself—a true Dean Winchester defense mechanism of projection. He worries about her so not to worry about himself. He tries to thrust the problem onto her so not to address the problem within himself—and fails at every step. It is clear that having her back is equally joyful and painful. He wants her safe, and he wants her around, but he fears that his joy at having her back will be short-lived. After all, he knows better than many that Mary’s words, “The thing is, hunters, no matter how good they are they all end up the same way,” rings true. He, himself, has met his own end in the pursuit of the family business. To have her brought back to life only to lose her in that enterprise would be worse than never having her back at all.

He tries hard to keep her safe again when they go to the house Lady Toni holds Sam hostage in. There, she is adamant about going into the house with Dean. She is their mother—both Sam and Dean’s—and she wants to help save one of her sons. For Dean, he wants to focus on saving one family member—on worrying only about one. And yet, as much as is this about her safety and his peace of mind, one has to wonder if this is also something else. Mary told him, “I’m your mother. You have to do what I say.”

For the past decade, Dean has been the one largely in charge. He’s the one making the decisions and calling the shots and assessing what takes priority. He’s been the eldest and the patriarch of the family for better or worse. The mantle of leader—rather he’s wanted it or not—has been thrust upon him since John’s death a decade earlier. Now, however, his mother has emerged, and she has no qualms about stepping up and asserting her own opinions. She doesn’t simply accept Dean’s authority. And unlike other authority figures that Dean struggles with, he can’t dismiss or brush off his mother. He respects her far too much to do so.

His stress about his mother’s return comes out in his reunion with Sam. Chained by Lady Toni and forced to become the new torture victim to coerce Sam into talking, he tells a stunned Sam that believed him dead, “I’m not sure that I’m not. I’ll tell you, I’ll tell you everything.” Despite being able to confirm her reality to himself, part of Dean fears that this is all an alternate reality or a strange afterlife. He can’t truly celebrate her return if he’s afraid that it’ll be ripped away all too soon or at any time.

In the aftermath of the rescue, as they sit around the Bunker’s table, Dean compliments his mother’s meal. She points out that it’s only take-out, but he won’t hear of it. After all, he tells her, “Your meatloaf was amazing.” Another memory meets reality because Mary tells him, “I would have cooked, but I don’t,” and that it “Came from the Piggly Wiggly. Sorry to burst your bubble.” Dean has spent years building a picture in his mind of his mother, and little by little some of it is shattering. He must find how those pieces will fit with the reality he sees before him—realign the version his four-year-old self remembers and the version he sees now.

Even so, Dean also shows that he is indeed much more comfortable than he, himself, thinks he is. His mother produces the one peace offering that would melt his heart: pie. She knows her son—even if he’s somewhat a stranger to her. He loves pie. Eagerly, the eldest Winchester dives into it without abandon. He slices a piece out and starts to ravenously eat it, thoroughly enjoying the sweet treat. It stuns Mary at how he’s behaving—and yet even when caught eating too fast, he boyishly just tells her, “No, no I cannot.” Dean goes back to eating his pie with enthusiasm. This is a beautiful moment—a celebration that his mother—and now his brother—are around him. He’s surrounded by family here and pie has always been tied tightly to that notion. Pie is comfort. Pie is love. To have his mother provide this pie signifies that she does indeed love him and want him happy. He is more than willing to indulge in that offering and show that he accepts all she’s giving.

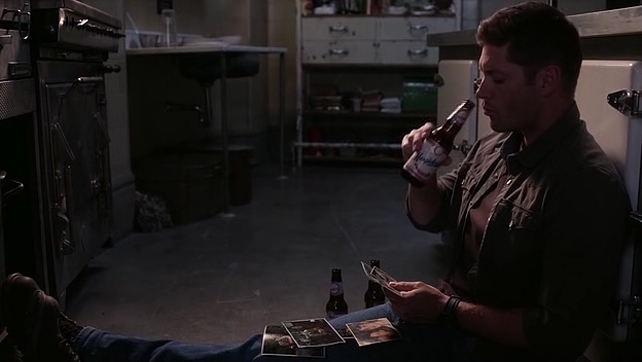

Dean still has a lot more questions than answers as of yet. He still has to fit his mother into his life and find his own place with her in the family dynamics. Dean starts this slow process in the Bunker sitting in the kitchen, looking through the old photographs of his mother and his family. He needs to understand where he’s been and where he’s going. How does he relate to her? What does her return really mean? How will they go forward? Even if these questions aren’t verbally raised, it is captured beautifully in his quiet contemplation here. She is back and he’s always wanted that—evidenced by how forceful he was about speaking (or not) about her as far back as the Christmas Sam learned the truth. The pain of her loss scarred his heart, and he now has a chance to heal the oldest of his wounds—but first he must learn to know his mother as she is and not as he believed her to be.

Sam, too, must learn to fit into their new family dynamic. In many ways, Sam Winchester has spent his entire life trying to fit into his family or the world around him. He’s tried to fit in with his brother and his father as they hunted through his childhood. He’s tried to fit in with the college crowd during his time at Stanford. Sam’s struggled to fit back into the world of hunting upon his return—while wanting to leave it behind, too. He had difficulty fitting in after his soul remained in the Cage—and again when it was returned. For Sam, he’s always tried to answer this most pertinent of questions, and once again he’ll have to do it with a whole new family member: his mother.

But before he can do that, he must get out of Lady Toni’s clutches. She will not leave him be, and she will not quit until she gets what she wants. Sam has little to no hope of getting out of this on the surface—all he thinks he has is his patience and stubborn refusal to give up. He has no idea about the rescue mission underway or the surprise waiting for him. All he knows is Lady Toni will resort to any dirty trick she can to get him to answer her persistent questions. Not one to betray the hunter community or the memory of his brother or his own integrity, once he breaks free of her most heinous and cruel method, he puts up a resolved face to refuse her what she wants. She’s violated him on fundamental levels. Sam Winchester may have helped her before she had done all of these terrible things—but now he will never will.

He needs to wait and bide his time for another try at escaping. If he can hold out, he’ll win. He’s beat her so far at every turn, refusing her the answers she desperately needs. Unfortunately, he doesn’t realize that Dean has found his location and has decided to go in for the rescue. The British Men of Letters have several tricks up their sleeves, and Dean is caught in an invisible one before it is too late, dragged in as the new tool in Lady Toni’s arsenal. If she can’t break his mind or his body, she’ll force Sam’s hand by breaking his brother in front of him.

Furthermore, as much as Dean struggled with their mother’s return and marrying his memories and the reality together, Sam has that same issue with Dean. He believes his brother to be dead—killed in the disarming of the Darkness. To have him shoved into this same hell hole with him and have Lady Toni threaten him must make him wonder if this is indeed his brother or not. He has little time to process that, however. Lady Toni quickly sets to test Sam’s resolve. Real or fake, it doesn’t matter. Sam will not sit by and watch Dean suffer if he can help it. He starts to crumble, his willingness to spill the names and locations just on the edge of his tongue.

Fortunately, though, Sam doesn’t have to betray the hunter community. The surprise ace up their sleeve bursts through the door and stuns him. Mary marches into the room and points her gun straight at the rogue British Men of Letters. As difficult as it was for Sam to believe his brother being alive, he’s most certainly finding his mother’s return stunning. He whispers in disbelief, “Mom?”

Sam has only managed to meet his mother once—when they traveled back to 1978 and tried to convince her to leave their father and prevent the Apocalypse. He had been emotionally drained by the experience. His mother, aside from that time, had only been a memory. The other encounters—both in his hallucinations and under the guise of Eve are not the same. Mary has always been brought to life in story and in other people’s memories. Sam doesn’t remember her singing to him or tucking him in at night or making soup for him when he was sick. He doesn’t remember his mother talking about angels. He doesn’t remember her bringing him pie. To Sam, his mother has always been a blank slate. He could have envisioned her any number of ways—pieced those stories together and made new ones all on his own to fill the void being a motherless boy provided.

Now, however, she is here in flesh and bone. She amazes him with her ability to fight and her devotion to protect her boys. Gone 30 years and she has no problem charging into a room to fight for her sons—even the one she only knew as a baby—the one she died above so long ago. Sam has always yearned for Mary—even when he didn’t voice it. Having her back sends ripples through Sam’s world. He now has to try and realign everything and find how he fits and she fits into this new family dynamic. This is his mother. This is the one person he’s probably needed the most in his life and now he has a chance to know her.

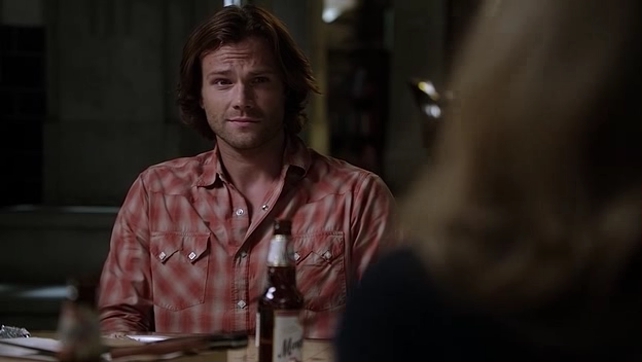

After they’ve returned to the Bunker, Sam quietly watches his mother and his brother. He has questions and wonders at what has happened since he left Dean to face Amara. And yet, as he watches their interactions—as Dean eagerly eats his pie—that Sam on some level has to feel a bit on the outside of that relationship. He has no history. Dean may have had an illusion dispelled by Mary, but he has none to refer to. The ice breakers for them are harder to grasp. Sam will have to start from a totally blank slate here and find a way to fit in with her. It’s perhaps one reason why Dean ends up in the middle at the table—a bit of a buffer.

His open staring does not go unnoticed by Mary, either. She tells him, “You’re looking at me like I’ll explode.” In some ways, that’s exactly what Sam might be thinking. Part of him is still coming to grips with the latest torture and mind games played on him. Having to confront the reality that his mother is here and alive must make him wonder and question if what he sees and hears is truly real. After all, long ago he was confronted by a specter of Mary while detoxing from demon blood—and the closing image of Sam staring at the fan recalls that painful moment. Another part of him wonders—just as Mary worried about Sam’s feelings towards her—how she must see him. How much she knows about his history and what he’s done and the guilt he still carries? None of this is voiced just yet, but it is etched all over his face as he absorbs what he has happened.

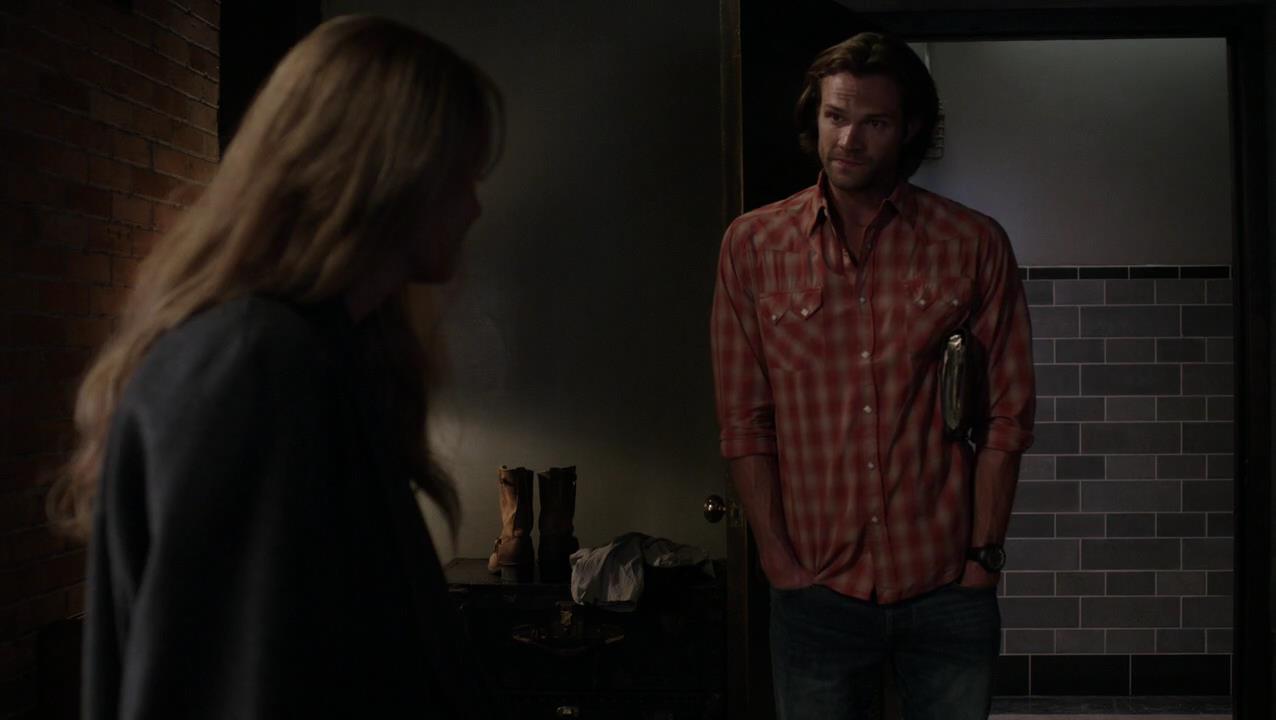

And yet, it is Sam that comes to her room, eager as the little boy he never got to be. He has brought her tea, unsure if she even drinks it. Sam smiles wide when his mother confirms that she does indeed drink tea. He approaches with excitement yet reservation. He doesn’t want to overwhelm her any more than Dean did—and yet he can’t help but visit her and take a moment to really realize that she is indeed here and real. Mary takes this in stride, amused by his eager entrance.

Sam, being who he is and knowing the hardships of resurrection after a long period, has no problem cutting through the small talk that has tongue-tied Dean. He simply tells her that they can talk anytime. And then, because he knows she must be mourning their father, he digs out another gift. It is fitting that Sam gives this to her rather than Dean. He has recently had his own bout with grief—even if it turned out to be short-lived—and he can tell that she’s struggling with the fresh loss. He tells her, “Dad’s journal. His writing, his words. Helped me fill in some blanks, answer some questions I didn’t know I had. And it you know, it keeps him with us. Sort of.”

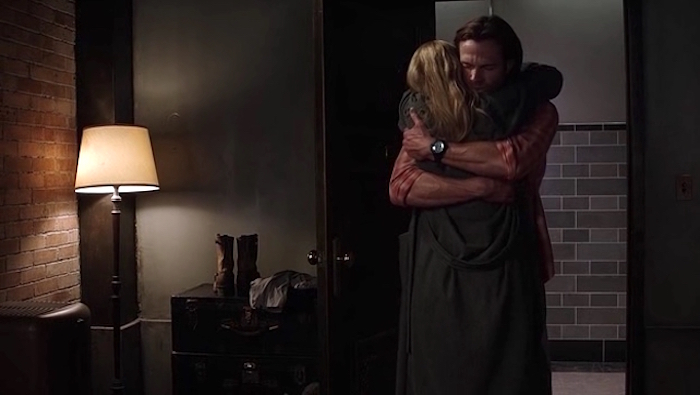

His gentle approach touches his mother deeply, and she hugs him, standing on her tippy toes to reach around his broad shoulders. Sam has never had a chance to really know his mother, and in this brief exchange, he has managed to bridge the gap of 30 years. Without really knowing her or what would help most, Sam found that very thing. By giving her a piece of her husband, by simply letting her know his door is open, and by allowing her space, Sam has allowed his mother into his own heart and shown that he will always be there for her. It is the most profound gift a son could give his mother.

Sam has taken a massive step on fitting into the new family dynamic. He has found a way to reunite with his mother—to build the foundation for the relationship he hopes they’ll have for many years to come.

Now that she’s returned, Sam will have to find a way to show her how they’ve been carrying on the family business of “saving people, hunting things.” He’ll have to keep reminding her that she does fit in with them—and that he doesn’t have any grudges for her deal. In fact, he’d be the last one to cast stones. If anyone could help her cope with her guilt or the weight on her conscience, it’ll be her youngest son. Sam has already proven that he’s up to that challenge—making the foundation of their relationship one of understanding and mutual respect.

He tells her, “Mom, for me. Just, um, having you here fills in the biggest blank.”

Perhaps that’s the answer Sam needs for now about fitting into this new family dynamic. Perhaps it is the only answer all three Winchesters need for the time being.

Leave a Reply