Singing The Sins of Creon: SPN’s S6 and the Prohibition Against Mourning

“You would rather throw stones at a mirror?

I am your mirror, and here are your stones.”

-Rumi, translated by Coleman Barks

A Beautiful Labor: The Work of Mourning

“The person who grieves, suffers his passion to grow upon him; he indulges it, he loves it” – Edmund Burke, On the Sublime and Beautiful

“The person who grieves, suffers his passion to grow upon him; he indulges it, he loves it” – Edmund Burke, On the Sublime and Beautiful

At the end of its fifth season Supernatural died, or at least one version of it did. The five year arc that began with the death of a mother ended with the death of a brother. The story organized itself toward a battle between destiny and free will, between redemption and damnation, between Michael and Lucifer, and it concluded in an appropriate setting: a hometown cemetery.

“Swan Song” marked the death of a story, and the following sixth season provoked an unusual but expected dilemma for both writers and audience: How do we read the next story – as rebirth or resuscitation?

As a viewer, season six has confounded me and part of that confusion comes from such a dilemma. Resuscitation averts death – skirts close to it but rebounds to a wholesome state. Resuscitation is elegant. Rebirth, however, is inelegant and clumsy – once something is dead, it is dead, and anything that comes back to take its place is different, never to be the same as that which died.

And this theme strikes at the heart of the Supernatural story.  The running notion of the “natural order” and what happens when humans upend that order are the stakes that the show raises again and again throughout its plot. And while the show follows the Winchester brothers, the story begins with the “unnatural” or “supernatural” death of the mother. So the emotion that most readily accompanies this upturned order is grief. The narrative, filled with the deaths of mothers, fathers, brothers, and friends, tries to perform the act of mourning throughout its first five seasons, but it often stops short of the ritual because death is deterred. As Dean once said, “I never should’ve come back, Sam. It’s not natural and now look what’s come of it. I was dead. I should’ve stayed dead.”

The running notion of the “natural order” and what happens when humans upend that order are the stakes that the show raises again and again throughout its plot. And while the show follows the Winchester brothers, the story begins with the “unnatural” or “supernatural” death of the mother. So the emotion that most readily accompanies this upturned order is grief. The narrative, filled with the deaths of mothers, fathers, brothers, and friends, tries to perform the act of mourning throughout its first five seasons, but it often stops short of the ritual because death is deterred. As Dean once said, “I never should’ve come back, Sam. It’s not natural and now look what’s come of it. I was dead. I should’ve stayed dead.”

The deferral of death dominates the storyline of Supernatural, and as a result, the mourning and melancholic nature of the Winchesters’ lives becomes the driving force of the plot. This notion also frames the show – and one should read mourning against the fifth season finale and the entirety of the sixth season storyline. Kripke was very adamant that his story had ended with season five; even going so far as to use the character of Chuck to part narrate/part eulogize his version of the Winchester story. But that was Kripke’s eulogy. It was Kripke’s interaction with his audience, with those who were following his story. As he bids his farewell, the door stands open, the grave remains unoccupied. The story dies, but yet it does not die. It comes back – reborn, reformed.

So what to take away from this new story, if it is new? Is it zombie? Is it real? Is it damaged? Can it be the same as it was? Or is it forever an imitation? And what to do with the grief for the story that has died?

Mourning forestalls the answers to these questions –  death answers itself, loss is loss. Freud once described the work of mourning as the work of detaching from a deceased object of love. Melancholia, on the other hand, draws on the work of mourning, but for an object that is dead emotionally but still physically alive. Melancholy, then, evokes a feeling of loss in the presence of the lost object. The end of Supernatural’s five year story opened the way to melancholy, for although one story was finished, another story appeared to take its place. A friend died; a friend remained.

death answers itself, loss is loss. Freud once described the work of mourning as the work of detaching from a deceased object of love. Melancholia, on the other hand, draws on the work of mourning, but for an object that is dead emotionally but still physically alive. Melancholy, then, evokes a feeling of loss in the presence of the lost object. The end of Supernatural’s five year story opened the way to melancholy, for although one story was finished, another story appeared to take its place. A friend died; a friend remained.

The social contract for Supernatural was based, in part, on the Kripke narrative on the Kripke vision of the Winchester story, so when he bows out of the community, how does that revise this tenuous social agreement? Rousseau wrote, “Each one of us puts into the community his person and all his powers under the supreme direction of the general will; and as a body, we incorporate every member as an individual part of the whole.” When a part falls away, what to do with the whole? Rousseau spends a lot of time contemplating how the social contract survives and flourishes, and even though his philosophy applies to a larger national scale, one can condense the experience to any community. The community surrounding Supernatural consented to a social contract with Eric Kripke; the contract centered on the Winchester story and the triumph of family over self, of choice over fate, of love over hatred, and finally, of brotherhood over the individual.

To my mind, the sixth season of Supernatural disrupts and prohibits the show’s audience from mourning the previous five years, an act which changes the terms of agreement in the social contract between Supernatural writer and Supernatural fan.

Bending Over Antigone: Dead Brothers and Female Mourners

Bending Over Antigone: Dead Brothers and Female Mourners

“The maid shows herself passionate child of passionate sire, and knows not how to bend before troubles.” – Leader of the Chorus, Sophocles’s Antigone as translated by RC Jebb

If the heart of the Supernatural story is brotherhood, then the heart of the Supernatural experience is the friendship among women. Over the years, the show has constructed a unique association with this audience, one filled with a sense of community that extends beyond the frame of the television screen. This community is acknowledged not only by the writers, but it is often (and increasingly) acknowledged within the text of the show itself. But the friendship, so far, has been based on a particular Winchester story, one that centered on brotherhood and clearly delineated what was wrong, what was right, what was monstrous, and what was worth saving. And although the show imagines (in The Real Ghostbusters) its fans as stacked with men, the most active fans of the show are women. And the end of season five cast these female witnesses into a role much akin to Antigone – the sister who is restrained from entombing the body of the brother. The show refused that process – there was no body to bury, no memorial to visit, no elegy to sing. Instead, the final scene of season five reveals the brother’s body restored, and with it the hope of rebirth.

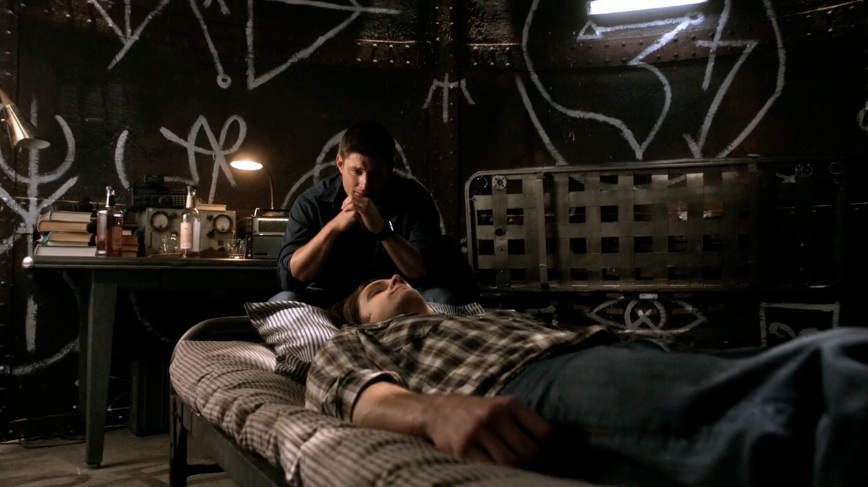

Jensen Ackles, as Dean Winchester, intuitively plays this anguish of deferred mourning throughout season six. Remember that Dean’s promise at the end of season five was the oath of to bring the brother back, an oath that we must read in the portrayal of Dean as he copes with Sam and his incomplete return. At the heart of Dean’s character stands a strong moral impulse toward justice and law, which is ironic given his illicit lifestyle.  However, law is not simply the letter. It is the spirit. And the spirit of the law in Supernatural tends toward ordering what has been disordered, which makes the task of following the brother into figurative hell all the more poignant and sad.

However, law is not simply the letter. It is the spirit. And the spirit of the law in Supernatural tends toward ordering what has been disordered, which makes the task of following the brother into figurative hell all the more poignant and sad.

Dean, whom I would argue is a stand-in for the largely female audience, carries the brunt of the emotional work at the beginning of season six and beyond. He never mourned Sam, couldn’t mourn Sam, for that would be the admission of death’s victory; refusing to mourn allows Dean hope but it also brings him melancholy. And the audience, who saw Sam, knew him to be alive, carries the emotional work of silent remembering. Both states invoke the ghost and bring into being the psychic trauma of witnessing without effect. In Dean’s pain stands the falling Sam; in the audience’s pain stands the reborn Sam. And neither can communicate with the other, so the disconnect is made real and verges on dramatic irony.

So Dean and the audience dwell in the same emotional space, one of aborted mourning, which is the stage for angst, an angst that Ackles commented on throughout the season in interviews. As a fan of the show, but even more importantly, as the portrayer of the character through which much of the pathos of the story is told and subsequently felt, Ackles intuits the dissatisfaction of the aborted mourning, even if he does not articulate it as such. The sixth season constitutes a performance of sorrow that is never quite fulfilled because the show itself cannot seem to accurately represent its own ambivalence toward the brothers and their story.

So the task of Supernatural’s sixth season, which had been the promise of that final scene of Sam looking through the window, soon reveals itself to be the opposite of return. There was no restoration, no rebirth. The body was the corpse made animate. The season, then, marked a renegotiation of the terms of agreement, or better yet, the social contract between audience and text. The story frame that had been the middle ground between audience and writer was purposefully disrupted. Brothers were reunited, but brotherhood was gone. The hunt continued, but the hunt became game rather than mission. And although love existed, it transformed into a series of moments that tore down the erotics of Supernatural and replaced it with the quiet sorrow of unrequited affection. Mourning becomes melancholy.

Noir is the Color of Grief

Noir is the Color of Grief

“Allow the claim of the dead; stab not the fallen.” – Tiresias, Antigone

If we use the road metaphor that the show has relied on for then we can see that the show’s first five years drove toward forgiveness and reconciliation, but the sixth season stopped at a crossroads and the turn it made took the story and its audience onto an alternative route where the moral and ethical rules from the previous seasons no longer applied. In fact, the sixth year of Supernatural became much like a photographic negative of a photographic negative, a copy of a copy. And the show, to my mind, made this turn on purpose and used the work of mourning as a way to re-frame its narrative.

By claiming film noir as its reference, the show made explicit its melancholy. The noir genre, as Tim Dirks (www.filmsite.org) defines it, depends on the themes of “melancholy, alienation, bleakness, disillusionment, disenchantment, pessimism, ambiguity, moral corruption, evil, guilt, desperation and paranoia.” Noir, then, overtakes the internal angst of the brotherhood, which had been part of the storytelling content and transforms that angst into a lens.

The effect of such a shift in the form of storytelling is immediate; the first episode of the season, “Exile on Main Street,” demonstrates the loneliness of Dean, the alienation of Sam, and the pessimism of a brotherhood lost. The final scene of this particular episode sees Sam drive off in another car, while the Impala hovers under tarp and memory in the garage, and Dean standing in the driveway watching his brother leave. The emotional impact on the audience could be interpreted as a double injury. The episode starts out with a montage of Dean within an unfamiliar context (home and hearth) and ends with Dean alone in an vacant driveway, an empty road. If Dean is the primary proxy for the mostly female audience, then his grief and guilt scaffolds the audience’s reading. The promise of this episode is a dark journey, one darker than any before because it begins with loneliness – a dramatic and decisive break from the pilot which had focused on the journey of a partnership.

At the other end of the journey, the season finale, which was nominally split into two parts entitled “Let it Bleed” and “The Man Who Knew Too Much,” fulfills the 22-episode agenda of emotional torture that moved the show into the realm of the melodramatic. Melodrama is a mode traditionally seen as appealing to a primarily female audience and often dismissed as failed allegory. Melissa Bruce, who used the Impala to examine the melodramatic in the first four seasons, argued that “By situating the Impala within the tradition of the film noir automobile, Supernatural places it specifically within a masculine space, while also using it as a symbol of emotion””a means through which the relationship between Dean and Sam can be read and understood. . . providing a stable and masculine space through which to explore the scenes of obvious emotion that so commonly pervade television melodrama.” (http://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/viewArticle/154/157)

Bruce’s observations become even more prescient when directed toward the sixth season, which not only employs noir as its narrative frame, but extends the claustrophobia that’s inherent in film noir outward past the cameras and into the audience it has long seduced while simultaneously held at bay. Noir becomes the “vehicle” that carries the intensely emotional stakes that are raised in the story and turns that into the frame through which the audience must experience the story. Taken as a whole, the sixth season can be read as a metaphor about what happens when the creator confronts not only what it has created but all of that which was created as a consequence.

The rippling pool bends back toward the thrown stone.

The allegory at play in Supernatural’s sixth season,  at least to me, then betrays a meta-level meditation on the nature of the show, but more importantly, on the nature of the interaction between show and audience. The dissolution of the fourth wall in “The French Mistake” reveals this allegory, in part, because the episode serves as a direct acknowledgement of the television show’s audience and not the internal audience of the books that had become part of the canonical storyline. Once the show dissolves the fourth wall, it builds a fifth wall which captures the audience in the plot, a kidnapping that had already occurred but now was recognized. And it is recognized in the most darkly humorous scene of the episode, the death of Eric Kripke.

at least to me, then betrays a meta-level meditation on the nature of the show, but more importantly, on the nature of the interaction between show and audience. The dissolution of the fourth wall in “The French Mistake” reveals this allegory, in part, because the episode serves as a direct acknowledgement of the television show’s audience and not the internal audience of the books that had become part of the canonical storyline. Once the show dissolves the fourth wall, it builds a fifth wall which captures the audience in the plot, a kidnapping that had already occurred but now was recognized. And it is recognized in the most darkly humorous scene of the episode, the death of Eric Kripke.

As stated earlier, the deferral of mourning is the subtextual stakes at work in the sixth season, but it is a multi-dimensional mourning. Dean’s mourning of Sam, the audience’s mourning of the core brotherhood that was disrupted and reneged upon, the show’s mourning of Kripke’s departure, and so on. “The French Mistake” concedes the complicated emotions at play with the character of Kripke, who is absent for most of the episode but still there in spirit, as ghost, until he finally arrives (somewhat reluctantly). His death marks a moment of candid interaction between audience and show. He is dead, the show asserts. But still the mourning is deferred, becoming comedy and invoking laughter. The outside hero of the show (Kripke) is destroyed, but that does not solve the problem of the hero within the show.

The noir-ish nature of the sixth season attempts to examine this narrative, but the problem comes in constructing a heroic figure in such a dark landscape. If the hero of the film noir genre is often alienated, then it is difficult to discern who the hero is in Supernatural: Dean, Sam, Castiel, or us? I would argue that the show itself is perplexed by this question. How do you go back and forward at the same time, while the audience participates, witnesses, and experiences the disconnect? Will they not find themselves as severed from the narrative as the other characters in the story have been?

Instead, by claiming film noir as its frame, the show betrays an+ inherent bias toward the dark. It further distorts the frame by seeming to divide the noir hero into two roles: Sam Winchester and Castiel. Sam, who remains soulless for the first half of the sixth season, challenges the audience’s previous expectations of the “good” Sam Winchester. Even when he was addicted to demon blood during the fourth season, his intentions were never portrayed as illicit or malicious. However, the soulless version of Sam Winchester navigated through the moral landscape of Supernatural without heed for the human cost of the hunt. As a noir hero, he fails since his ambiguity is never quite fully achieved and his actions become increasingly robotic – the noir hero must have a soul, must be human, in order for him to feel the true heaviness from the moral weight pushing down upon him.

Instead, by claiming film noir as its frame, the show betrays an+ inherent bias toward the dark. It further distorts the frame by seeming to divide the noir hero into two roles: Sam Winchester and Castiel. Sam, who remains soulless for the first half of the sixth season, challenges the audience’s previous expectations of the “good” Sam Winchester. Even when he was addicted to demon blood during the fourth season, his intentions were never portrayed as illicit or malicious. However, the soulless version of Sam Winchester navigated through the moral landscape of Supernatural without heed for the human cost of the hunt. As a noir hero, he fails since his ambiguity is never quite fully achieved and his actions become increasingly robotic – the noir hero must have a soul, must be human, in order for him to feel the true heaviness from the moral weight pushing down upon him.

With that said and given the full order of episodes in season six, I would state that Soulless Sam was the show’s bait and switch con on the audience. He was offered as the noir hero, when in point of fact, the angel Castiel was waiting in the wings to ascend to that role. In other words, the switch between Sam and Castiel was the corruption that upon which film noir capitalizes. The corruption of the hero, which weighed heavy on the classical hero of the story (Dean Winchester), further alienates the audience from the plot but perhaps this is the beginning of the mourning, the road that leads us away from melancholy and toward sacrament. At the end of one story a god-author says farewell. At the end of another, a character becomes a new god – the story takes itself back from the outside.

And perhaps, the corruption of Castiel is the bend back toward a Winchester story. Perhaps this return demands the sacrifices that have been readily made. The story is folding back toward the center, and now fully embraces the audience in its turn. Perhaps the edge of the world, the edge of the story, has finally been seen, the deaths have been acknowledged and the tombs have been opened.

Maybe now, the rippling pool can touch the thrown stone.

Bring Out Your Dead. Bury Your Beloved.

“Be of good cheer; thou livest; but my life hath long been given to death, that so I might serve the dead.” – Antigone

In the end, my reading of season six is one of hope rather than sadness. The terror of grief is that it undulates and folds back on itself, which extends its life and heightens its passion. Mourning is not only acceptance; it is the recognition that acceptance is necessary to move on. The audience reception to the sixth season of Supernatural demonstrates the power of grief and the problems in deferred mourning. When a community has reciprocated affection based on one set of rules, it is difficult to transfer that affection to another without a certain amount of resistance. The show uses the sixth season not only to tell a story, but to also tell the story of the story, to assist its audience in making the move beyond, the move toward something else.

Was this its intention? Probably not, but it was a result. To prohibit mourning is a dangerous game, as Creon sees in Antigone. The dead command the attention of the living just as much as the stage commands the attention of its audience. Season six, then, can be read not only as story but as meditation on what it means to mourn the beloved, but not alone, rather in the presence of the whole community. Even in your grief, you are not alone. At least, that’s the sixth season for me.

on the side of the road.”

Rumi, as translated by Coleman Barks

Excellent interpretation and a very good read. I look forward to the new thing in Season 7 and the fruition and return of the natural order.

And what to you is Sam in this whole story? a vehicle for the audience or Dean?. Dean doesnt mourn for Sam because it would admit death won to Dean so when does Dean mourn for his brother ? when he is dead? souless or is Dean really mourning for himself at what he lost not what Sam lost.

A very interesting read by the way but like I say looing at it and the series has a whole it leaves me wondering exactly who or what Sam has meant to be to us?? Dean?? the story? .??If we see Dean has a classical hero how do we view Sam ?And where does Sams own mourning for his loss fit in ??.

Great question, Ellie. This is actually a shortened version of a longer paper, in which I do address Sam. To me, Sam is the object of the audience’s affection, which is why I made the observation, to me at least, that Dean acts as the lens of the story.

Also Sam, for me, is the embodiment of mourning, for his life is really a study in missed opportunity, deferred futures. He makes it possible to see that all the potential futures that could’ve been, which is why the whole alternative universe happening in season six with Sam accentuates this. I think, especially in the season finale, the possible Sams underscore this observation, which has historical precedent in the story. Here I think of a few things: (i) his presence is the moment of the mother’s death, (ii) his choice to leave for Stanford is the grasping for another future, (iii) his sacrifice to Lucifer changes the outcome of the SPN world. So I guess what I’m trying to say is that although Dean and the audience perform the mourning, that Sam is actually embodied mourning, if that makes sense….which makes the character of Soulless Sam even more poignant; it’s like another injury.

Bookdal, thank you ever so much for this excellent article. It’s one of the best meta-articles I’ve read in a while, and each segment was a joy to delve into.

As I read it, you looked at season six as a painting of various faces of mourning and the results of it and the DNA this show borrowed from film noir (which you love, I know 😉 )

Did I mourn? I think I did, but only a little… my love for this show didn’t hurt, though the story sometimes did. I’m not brave when it comes to watching (or reading about) characters I’ve grown to love – when they suffer, my tears come. Sometimes even in their stead, I think sometimes.

Again, I enjoyed this very much. Thank you!

Take good care, Jas

Thank you so much Jas! You know that I admire your interpretations and readings, so I take this as the highest compliment.

As for the mourning, I think we have this sympathetic contract with the show, and it’s hard not to feel their pain, especially when we have grown so fond of them.

It’s me, now, who wants to say: Thank you!

🙂 , Jas

Wonderful interpretation of Season 6.

I agree that this season ended not on a sour note of dread or despair but one of hope. Castiel may have ended the season with his declaration, but we are left with a newly reformed and reborn Winchester brothers and it took this dark path for them to find the light.

This season has brought us, the audience, in as participant more than any other. I agree that Dean was our representative for much of the season. Since he is the vehicle for which we see the story and we share his feelings about Sam and hunting and life and everything else unfolding before us, it only makes sense that he is our mirror. We are unsettled when he is unsettled. We hold back our tears when he does the same. We feel his unease—a testament to both the skill of the writing team and to Ackles for presenting it as such.

I do think, though, that this season not only steered away from the mourning some might have expected after “Swan Song,” but pushed us into a new direction that can give both the Winchesters and us the audience a new and different path. They are no longer stuck under the frame of destiny. By “ripping up the script” in averting the Apocalypse in the fist place, they now have the ability to venture into new and uncharted territory.

To get there, however, we had to walk in the shadow and mystery. Each step was not laid out before any of our heroes or villains, something that everyone from Crowley to Balthazar mentions. It’s also the most dangerous path to walk because it isn’t plotted and no sign posts will give direction on which is the next step or right path. Each step could lead to despair or hope—the trick is to find which one does what. Season’s 1-5 largely gave us a two forked path of options—until they decided to avert the script. They could have done all destiny had scripted (both brothers could have said yes and had the prize fight; Sam in season 3 could have been the leader of the demon army, ect) or they could have continued resisting until the world was destroyed. By choosing to ignore either path and write their own it makes sense that season 6 would delve into those dark and sometimes convoluted consequences.

I do think we are seeing a turn towards hope. That the dark path they are on will find that needed illumination—that the contract that the center of the show is being reborn in a newly forged and strengthened bond between Brothers Winchester. It’s all coming together and leading us down a new road.

Thanks for this wonderful meta look. It’s been awhile since I’ve delved into the actual discussion of noir—not since college six years ago!

“By choosing to ignore either path and write their own it makes sense that season 6 would delve into those dark and sometimes convoluted consequences.”

This is it exactly! I love this observation – season 6 was this watershed year, where the storylines from the past transformed into other storylines, which were consequences.

And you’re right – the dark leads to the light, or at least that’s what I expect.

Thanks.

Having rewatched the season now through “You Can’t Handle the Truth” and thinking about what got us to season 6, it just occurred to me that this is a portion of what they sowed and now must reap.

I firmly believe they’re leading us and the brothers into the light. There’s a lot of darkness in the last two episodes, but that fire imagery and the reforging of that brotherly bond is that candle flame we need to provide hope.

Is it September yet?

Thank you, Miranda. I’m anxious to see what’s in store for Castiel as well.